Blog

Published on VoteWatch.eu.

Update: the European Parliament decided on 9 June 2015 to postpone a crucial vote on TTIP, due to extremely high number of amendments and big uncertainty regarding the outcome of crucial votes, as we predicted several months before. Here is an updated version of our projections.

Note: this analysis has been read by over 6.000 people, mainly experts, in the first 3 weeks since its initial publication in April 2015. It has been recommended by specialised institutions such as the Atlantic Council, Johns Hopkins University, AmChamEU and senior EU politicians.

—————–

Almost 900 amendments have been drafted at the committee stage to the European Parliament’s position on the ongoing negotiations conducted by the Commission for a Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership with the United States (TTIP). In plenary, yet another round of amendments was drafted by the political groups, in such a big number that the votes had to be postponed, increasing the unpredictability of the outcome of one of the most crucial dossiers the EU is currently managing.

Although the European Parliament is not formally involved in negotiations, the European Commission is legally obliged to keep Parliament updated, and Parliament has the power to reject the trade deal once it has been finalised. As seen in the case of the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA), the rejection of a done deal is not only a theoretical possibility, but can turn into reality if a (political) majority of MEPs disagree with the content of the deal, or the low level of transparency of the process. Before the actual ratification vote, the Parliament usually votes, once or more times, a non-binding resolution stating its position and the ‘no go’ zones, as is the case of the resolution currently being worked on in the international trade committee (INTA).

The immediate consequence of this avalanche of amendments was that the votes on this document had to be postponed, to allow time for proper assessment of all proposals. The text passed the INTA committee stage on 28 May and was expected to be voted upon on 9 June in the EP plenary, exactly two years after the EP voted its last resolution on TTIP. However, the plenary vote was postponed.

TTIP has generated an unprecedented lobbying activity as both the proponents and the opponents of the deal aim to form ad-hoc coalitions and rally as much support as possible among the MEPs, to ensure majorities in favour or against the most contentious provisions of the text.

What are the starting positions ?

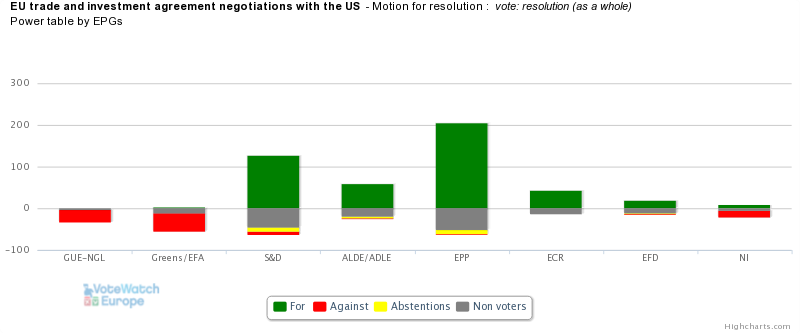

At this point, based on the previous voting record of MEPs corroborated with the results of the EP elections in 2014, one could foresee that a majority of EU parliamentarians are in favour of TTIP in general. In May 2013, a comfortable majority of 460 Members (78%) voted the ‘go ahead’ for the start of negotiations. These came from among the groups of the European People’s Party (EPP), Socialists (S&D), Liberals and Democrats (ALDE), Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and the Eurosceptic EFDD group.

The only ones opposing at that time were the radical-left and green Members, as well as most of the non-attached nationalists. Interestingly, however, a small minority of MEPs in the big groups did not support the mandate: the Hungarian EPP delegation (coming from Viktor Orban’s party, who had started at that time to have differences with its European and American counterparts) and the French and Belgian French-speaking socialists (traditionally the most protectionist from among all S&D Members).

Here is the breakdown of the final vote:

What are the predictors of an MEP’s position ?

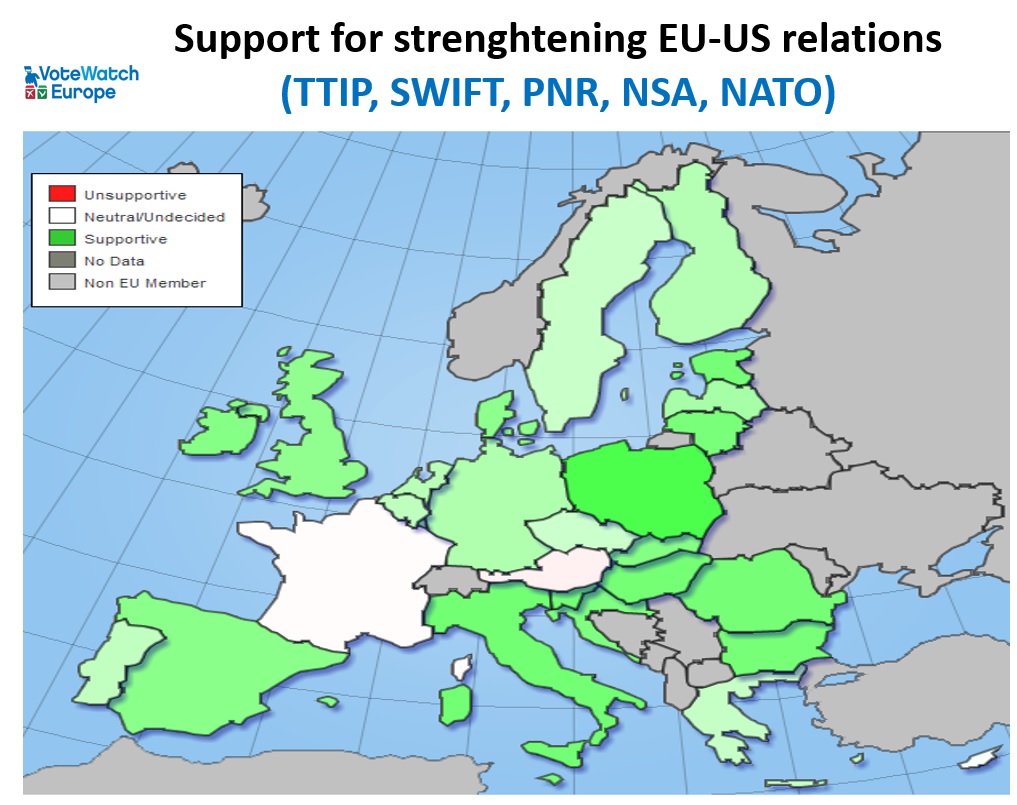

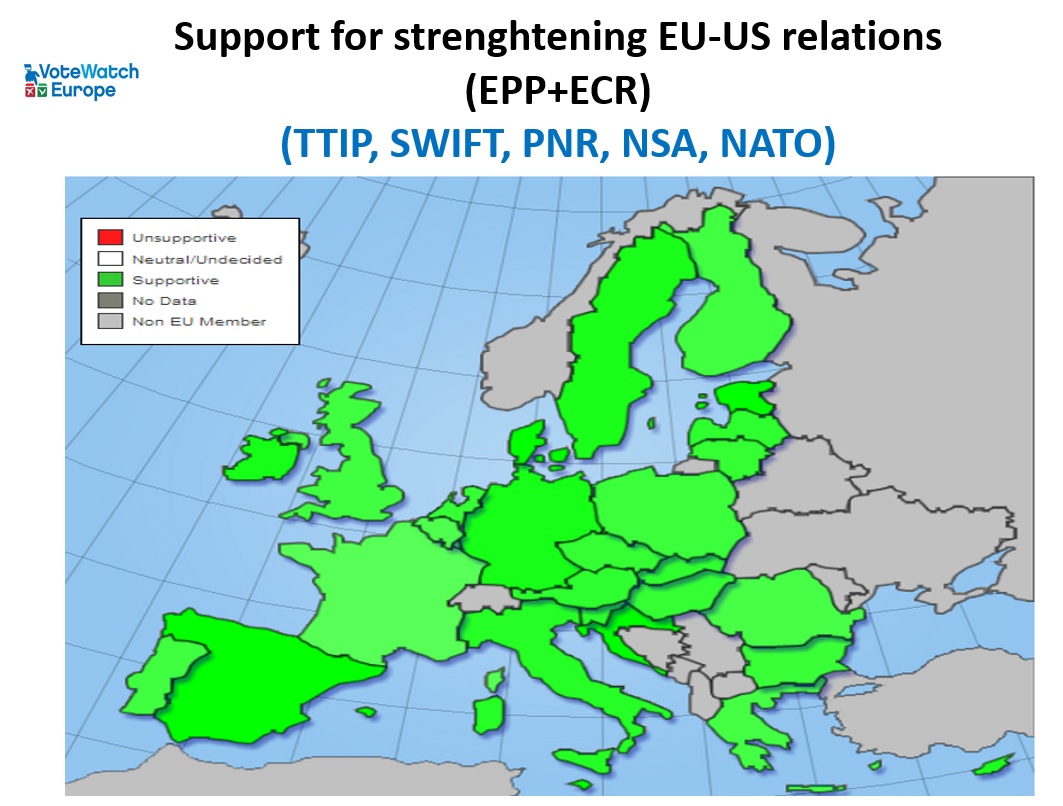

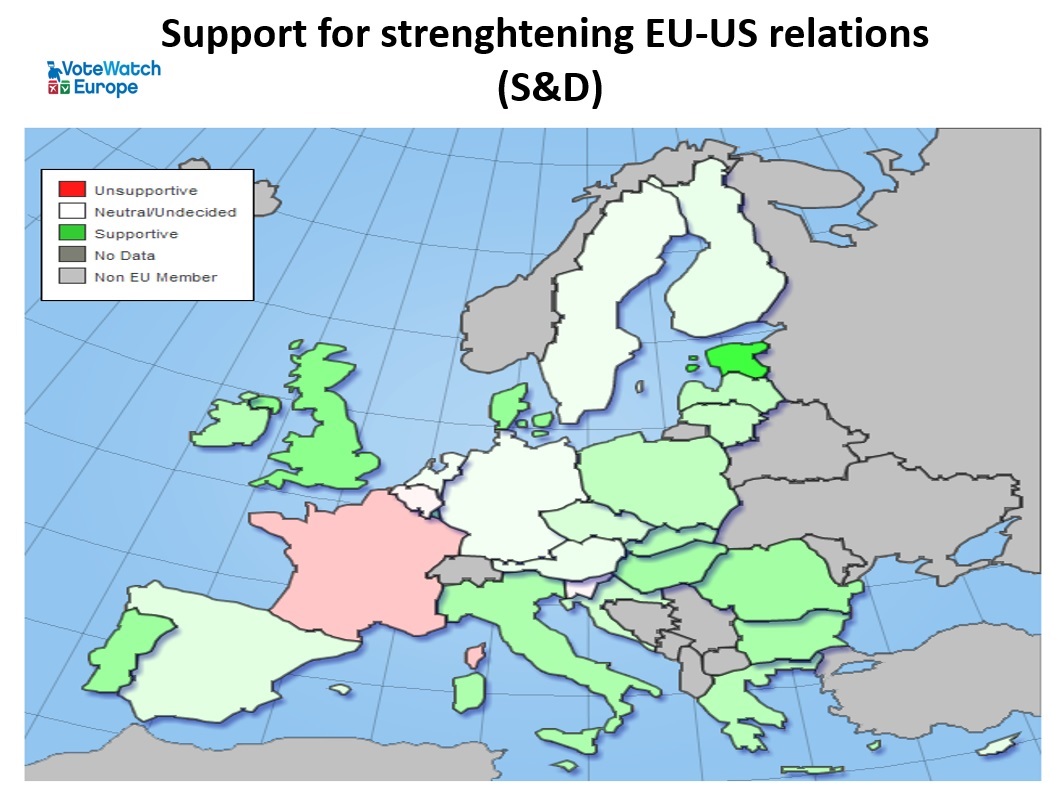

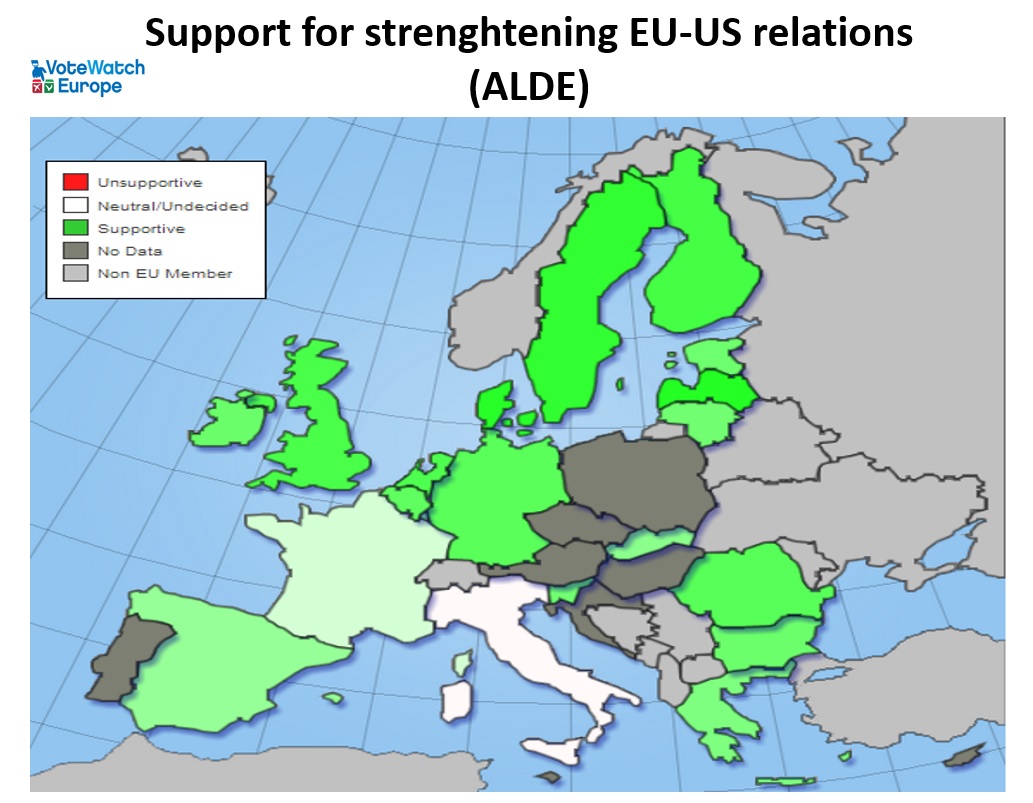

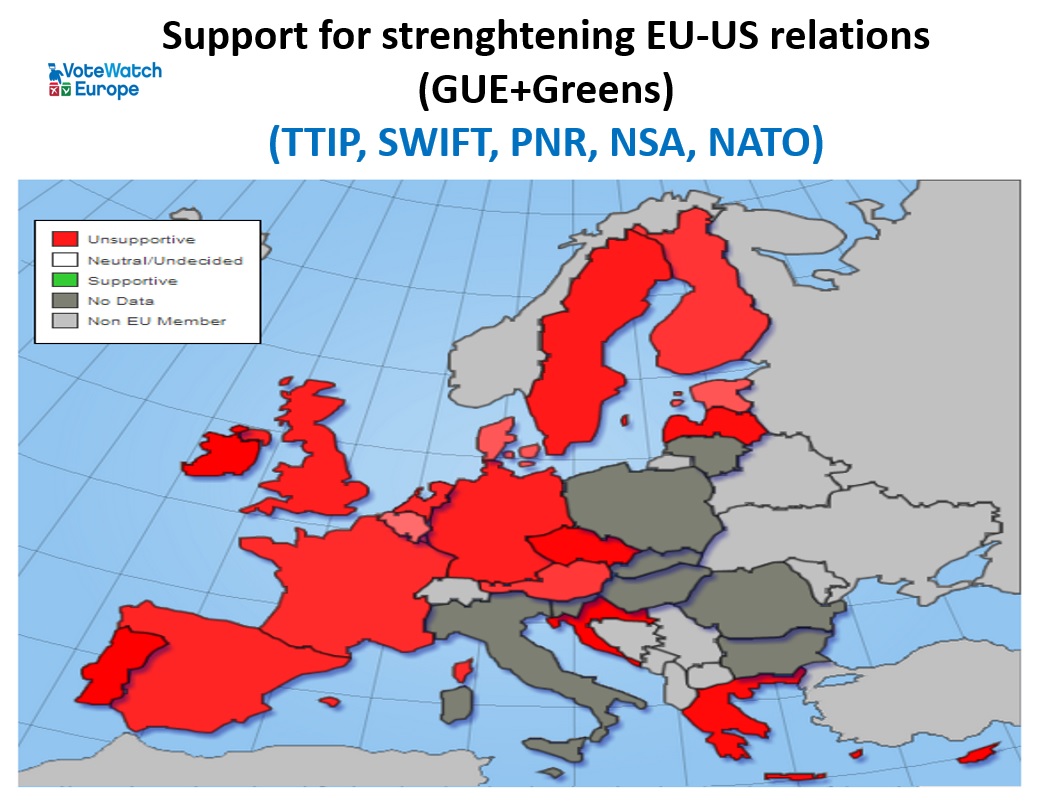

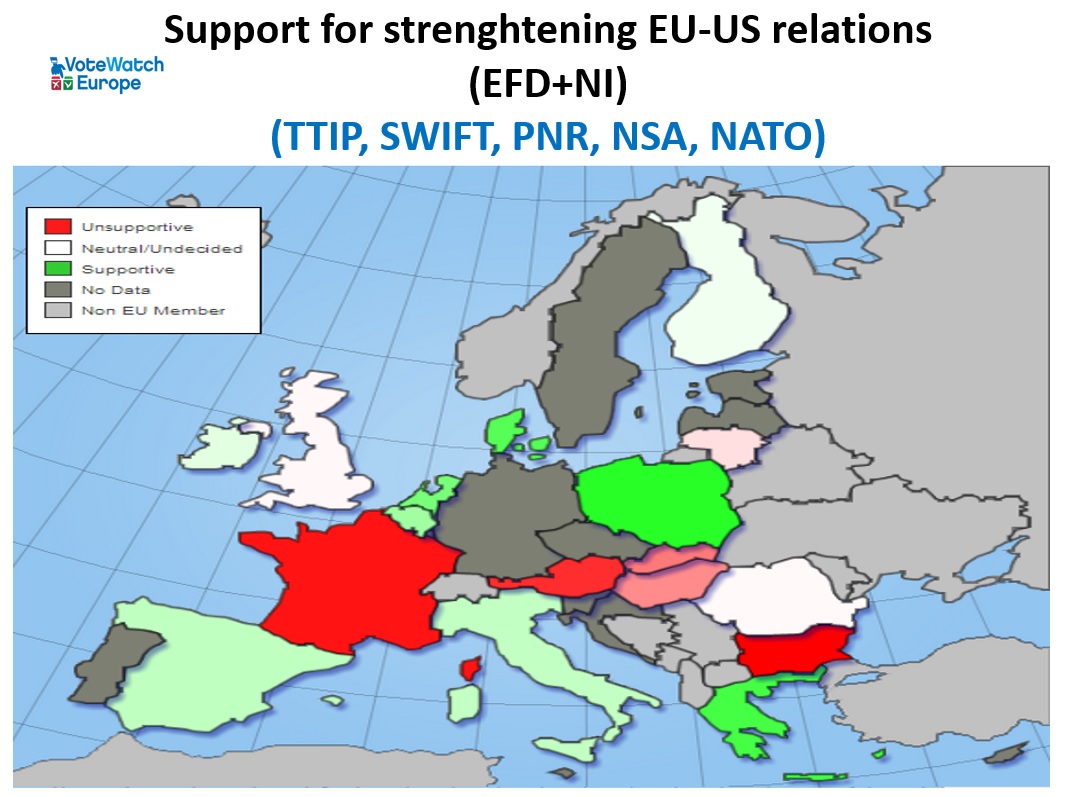

There are two key indicators that can be used to predict how an MEP will vote on TTIP: his/her inclination to vote in favour of free trade in general, and his/her inclination to vote in favour of good EU-US relations in general. If we look at the EP as a whole, the lowest level of support for good EU-US relations (measured as analysis of the MEPs’ votes on dossiers related to TTIP, SWIFT, PNR, NSA, NATO) is recorded among the French and Austrian MEPs, while the highest is seen among the Eastern European states (recent NATO allies) and the UK.

Naturally, ideology plays a fundamental role, as the centre-right EU politicians share, on average, more of the US views and ways of doing things in the economy, society and in foreign affairs, compared to EU left wing politicians (i.e. the more you go to the left, the stronger the opposition to US policy and views). This can be attributed to the fact that the US is seen as a model that promotes free market, individual achievement and competition, values supported primarily by the centre-right in Europe. On the other hand, EU left-wing politicians have reservations concerning the US proposed approach on social standards, hence their comparatively lower level of support to the US in general.

This pattern can easily be spotted by looking at the breakdown of pro-US positions across dossiers, by political groups (data from the 2009-2014 term):

What has changed compared to two years ago ?

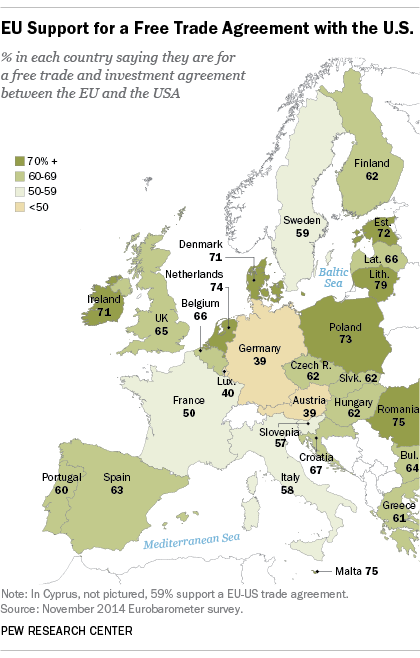

In parallel to the debates and trade-horsing inside the EU institutions, a fierce campaign for generating public support / opposition is being fought by the two sides, whose results may impact on the voting behavior of the MEPs. Since the start of the negotiations, the ‘no’ camp seemed to be much more active in the public arena and this has not remained without impact on the public opinion. The countries whose populations seem to be least convinced about the benefits of the TTIP are Germany, Austria and Luxembourg[1]. On the other hand, the surveys show that the majority of the public is still supportive of the TTIP in the remaining EU countries, with a peak in two ‘new Europe’ countries Poland and Romania (these countries have been in general highly supportive of strong transatlantic relations ever since the fall of communism in 1989). The public in the Netherlands, Denmark and Ireland is also highly supportive of the TTIP.

Despite this development, the MEPs that believe that TTIP should be stopped altogether will remain a small minority. The radical-left (reinforced after EU elections) will still oppose, as will the non-attached nationalists such as French Front National and some of their smaller counterparts in the other countries. The Greens/EFA will most likely be unsatisfied with the content of the deal and also oppose it. And so will part of the EFFDD group, more precisely the Italian 5-Stars Movement. Some small factions in the big groups may also not be happy with some of the provisions, and defect from the group line. However, a comfortable majority in favour of TTIP as such will remain.

What will happen to the ISDS: a softened mechanism will eventually pass

On the other hand, key provisions in the TTIP will be under heavy fire and their outcome is uncertain. Chief among these is the investor-to-state clause, a mechanism which allows investors to settle disputes with national governments in international courts, rather than national ones. On this particular matter, the ideological footprint of the Members can easily be spotted: the more you look to the left, the stronger the opposition to ISDS, and the other way around. The radical-left, the greens and the socialists look set to oppose it, on the ground that this undermines the power of the public sector / state to regulate. The EPP, ALDE, ECR (and the UKIP) favour ISDS, arguing that independent courts are necessary so that private investors to feel confident enough to take the risk of investing in a foreign state.

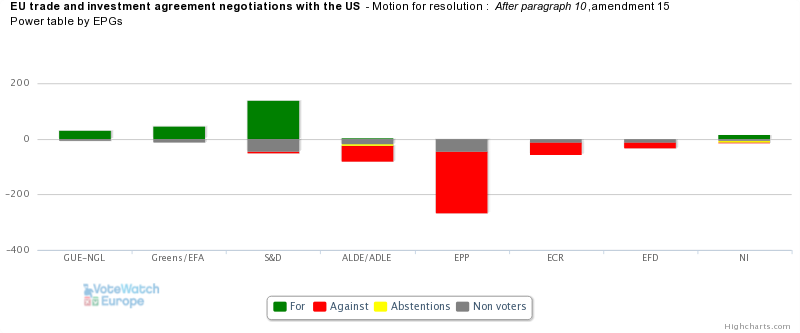

Two years ago, the pro-ISDS camp won. A call to exclude the ISDS from the TTIP was rejected with 233 votes in favour to 352 against. Here is the breakdown of votes in May 2013:

However, the pro-ISDS camp has lost a considerable number of seats in the EU elections (EPP alone has lost around 50 seats), while the anti-ISDS camp has gained, which makes that the balance of power among the MEPs is now extremely fragile on this topic.

Aware of this (and also reacting to the pressure from the pro-social sectors of the public), the Commission has promised to reform / soften the ISDS to make it more public sector-friendly. In this way, it hopes to convince part of the opposition to change camps, or at least not actively oppose.

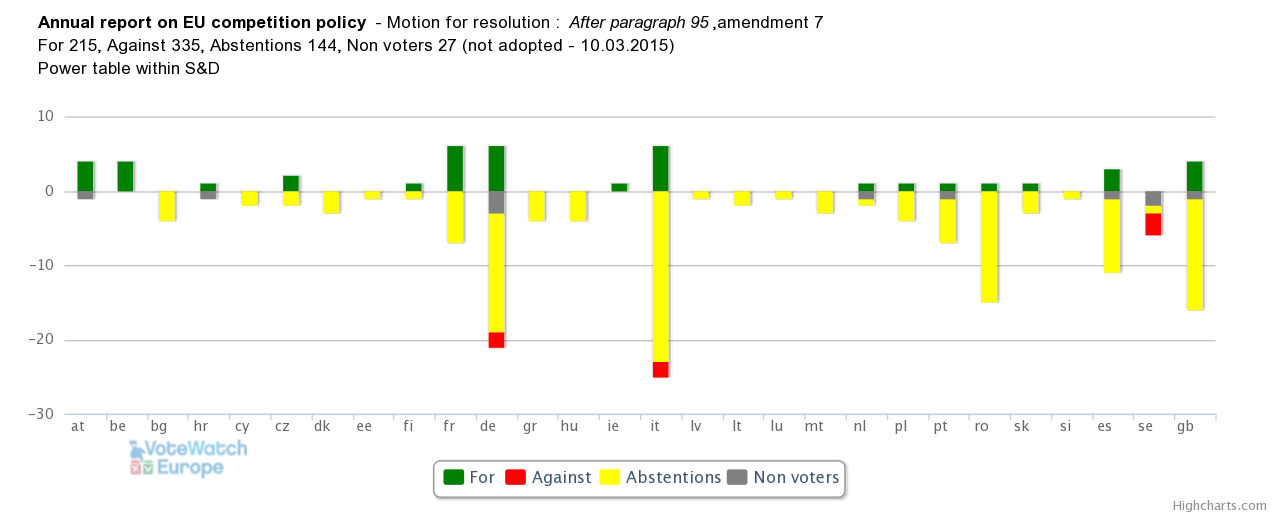

Traditionally, the British Labour delegation has been the most in favour of free market within the S&D group, but Labour has clearly stated its opposition to the ISDS. The surprise might come from the German SPD delegation who, even if it has been initially firmly against ISDS, Germany’s SPD Economics Minister, Sigmar Gabriel, seems to have soften his stance lately, as he is part of the ‘grand coalition’ in Berlin (it’s worth noting that half of the German SPD MEPs have not been present at the vote on TTIP two years ago).

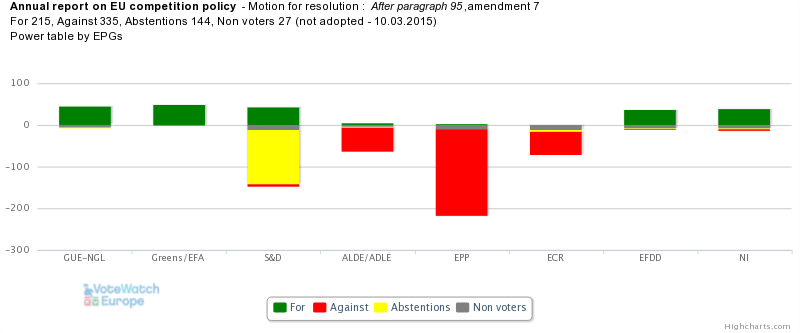

At the beginning of 2015, the positions of some of the socialist national delegations in the European Parliament have started to soften, which has led to fierce internal disputes. In a vote on EU’s competition policy, the S&D group experienced its first (dramatic) split on ISDS. The key amendment (number 7) said:

[EP] Stresses that the use of investor-state dispute settlement in free-trade agreements serves to remove the democratic right of Member States to implement their own policies;

Here is how the groups voted on this provision:

And here is the break down by national delegations in the S&D group:

Moreover, through the softening of the ISDS provisions, the Commission aimed to secure the support of and mobilise some of the EPP national delegations who might have otherwise become hesitant under pressure from the pro-social civil society, particularly the German delegation (which is also the largest), but also the Italian one (almost half of the Italian EPP delegation was absent from the vote who took place two years ago on TTIP).

If EPP Members are mobilised and a decent number of S&D MEPs break the group line (or simply don’t vote), then a narrow majority will push through a softened ISDS. However, the exact phrasing and the internal horse-trading will certainly play a role in the outcome. Moreover, even if a provision supporting the ISDS is passed in June 2015, the balance of power may still change before the end of the negotiations and the ratification by the EP, if the ‘against’ camp becomes more successful in convincing and mobilising the public opinion, exactly as it happened in the case of ACTA (who initially had the support of a narrow majority in the EP, but in the end the tide turned overwhelmingly against it).

Be the first to post a comment.