Blog

MEPs from the pro-EU groups have made a very bold move this week, asking for fundamental changes to the way the European elections are to be conducted from now on. If these are adopted, in 2019 we will witness a very different kind of European elections, much more similar to the national ones, which would enhance the legitimacy and the power of the MEPs and of the EU institutions as a whole. However, important political players are yet to be convinced.

Key reforms wanted

The proposals are meaningful and in line with the efforts of the Members of the EU Parliaments (MEPs) to make the elections more European. EU parliamentarians have asked that the spitzenkandidaten process, which was experimented in 2014, be enshrined into law and that political families should come up with their nominees with at least 12 weeks before the elections. Moreover, a new EU-level constituency is to be created, in which lists are to be headed by each political family’s nominee for the post of President of the Commission. A threshold of between 3% and 5% is to be introduced in larger constituencies to avoid too much fragmentation in the European Parliament.

The names and the visual identity of the European political parties are to be promoted in the electoral materials at national level to enhance the European dimension. Gender equality is to be observed and the voting age should be lowered to 16 years old.

The political process: unanimity needed in the Council

The Treaty (art. 223/1 of TFEU) gives the European Parliament the right to initiate a reform of the European electoral law by formulating proposals, which the Council will have to decide upon by unanimity. Then, the amendments to the European Electoral Act are submitted for ratification to the Member States according to their constitutional requirements.

With the proposed reform, the rapporteurs aim at increasing the democratic dimension of the European elections and reinforcing the Union citizenship. They wish to improve the functioning of the European Parliament and make the work of the Institution more legitimate.

Positions of the key political players

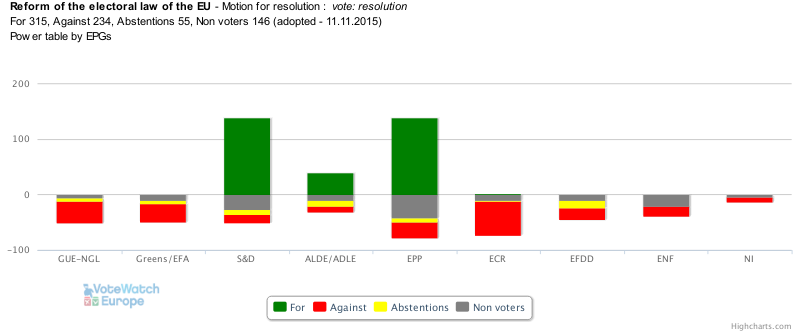

The text is the brainchild of two rapporteurs from the main EU political groups, Danuta Hübner (EPP -PL) and Jo Leinen (S&D-DE). It is highly significant that the report has bipartisan support (centre-right and centre-left), which means that most of the governments of the member states will be lobbied through the parties’ networks. The report was voted through the EP plenary with 315 votes in favour to 234 against, with 55 abstentions.

However, the proposals meet the opposition of strong leaders. Firstly, there are the British and Polish Conservatives, who govern on their own in London and Warsaw and whose MEPs voted against the above-mentioned reforms. Notably, the British EU Parliamentarians from across the political spectrum, not only David Cameron’s conservatives and Nigel Farage’s UKIP, but also the Labour and the British Greens voted against making the European elections more “European”.

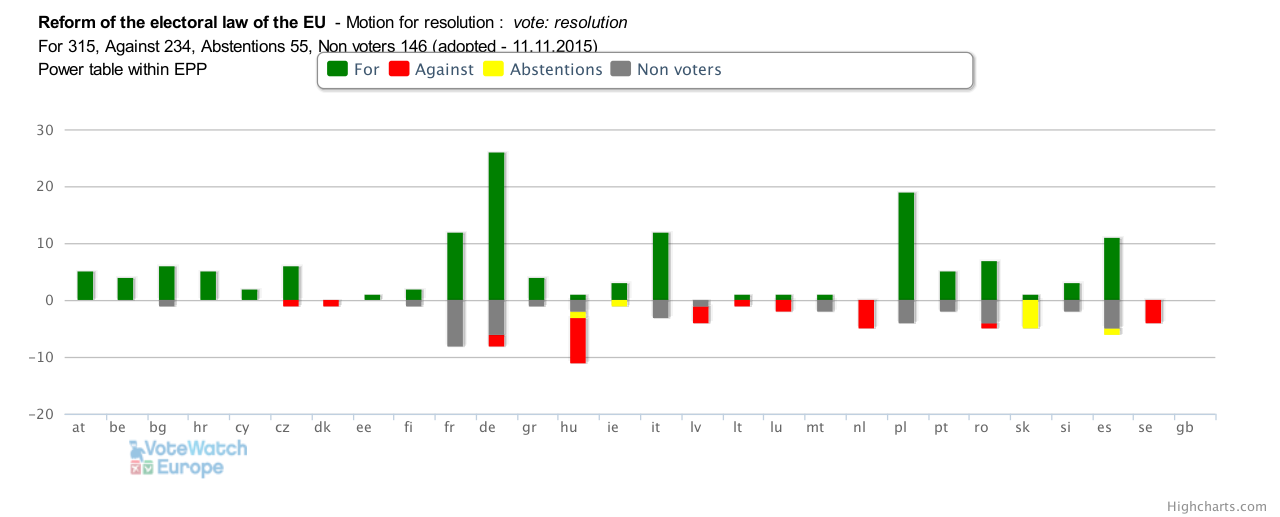

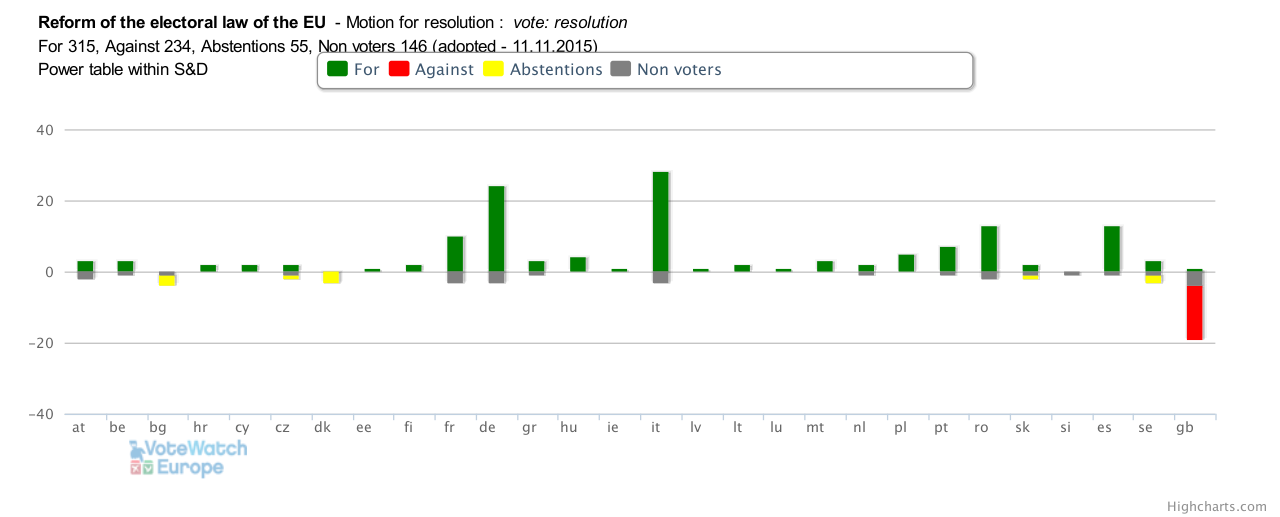

Secondly, even within the People’s Party and the Socialist groups there is opposition, as shown by the votes. Within the EPP, the strongest opposition comes from the Hungarian delegation of Viktor Orban, whose position seems to be drifting further away from that of the EPP (and more towards that of the ECR). Their Latvian colleagues, part of the main governing party in Riga, also oppose. Then come also the Swedish conservatives who, even if less vocal, have reservations towards strengthening the EU. Their position is less relevant for now, as they do not control the Government in Stockholm, but those who do, their Socialist fellow countrymen, also expressed strong reservations in the EP voting session. The same goes for the Dutch CDA/EPP Members.

Significantly, two out of the three Luxembourgish party colleagues of Commission President Juncker voted against the reforms (the third one, former Commissioner Viviane Reading, was the only one who voted in favour).

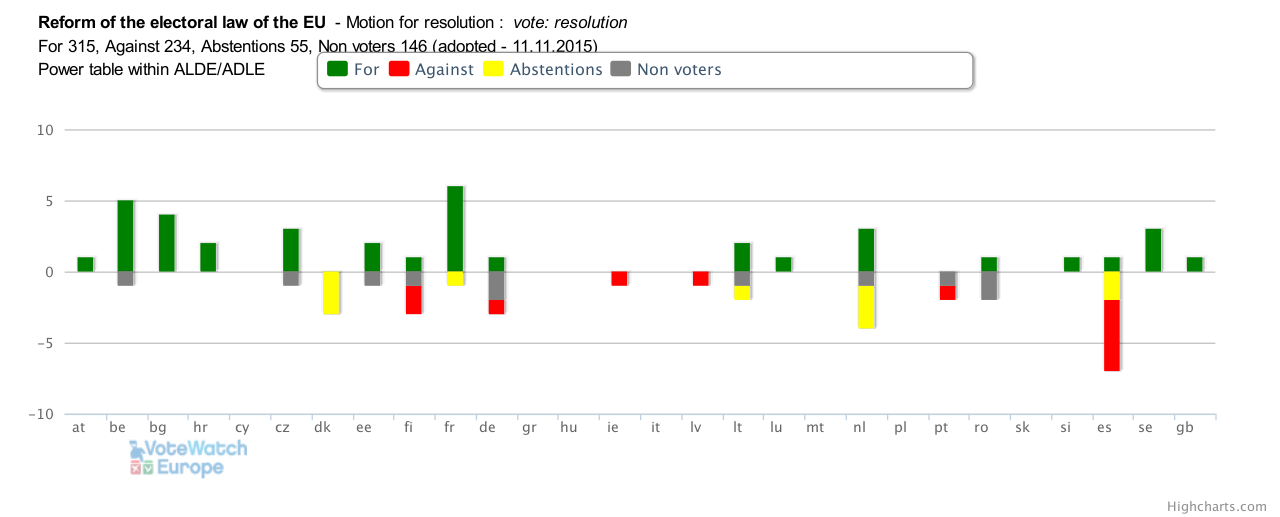

There might be one “little” obstacle in the liberal ALDE camp too: the Finnish delegation, the party of former Commissioner Oli Rehn. The opinions within this delegation are mixed.

Voting behavior on key parts of the reforms

EPP sided with eurosceptics and voted against giving equal prominence to European political parties and national parties

One key provision (amendment 7) was asking that the European political parties receive equal visibility with national parties on the ballot papers, in the media and on electoral campaign materials. This proposal fell in the plenary, as the majority of the EPP group and a minority of the S&D and ALDE groups voted against it. Within the EPP, those in favour of this bolder move towards the europeanisation of EU elections were the Austrian delegation, a few German and Portuguese Members, the rapporteur Danuta Hubner and EPP’s vice-president Marian-Jean Marinescu (RO). EPP’s chair, Manfred Weber, voted against it. In the Socialist group, those who opposed to giving equal visibility to the European political parties were the British, Danish and Swedish delegations, while in ALDE were the Finnish and some of the Spanish Members.

However, the EPP group did back the principle that the logos of the European Parties should be on the ballots and electoral materials. A minority of ‘radicals” in the EPP group voted even against the idea of having these logos at all: these are the Hungarian, Slovakian and Swedish EPP Members. British and Swedish Socialists also opposed. Notably, even within the Greens group, otherwise known for its cohesion and pro-European stance, the British and Swedish greens voted against having European party logos on the electoral materials. The radical-left communists were split down the middle on this subject: 20 voted in favour (Germans, Greeks and Spaniards) and 20 against.

Gender equality on the list is desirable, but not through alternation of names

A strong majority of MEPs voted that the list of candidates for election to the European Parliament shall ensure gender equality (amendment 43/1) starting with 2024. However, a very narrow majority (295 “for” to “304 “against”) rejected the proposal (43/2) that this objective “shall be achieved in all Member States by zipped lists, or other equivalent methods” (zipped party lists mean that names of females and males would alternate).

Voting age should be lowered to 16

As a future step, EP recommends to Member States that they should consider ways to harmonise the minimum age of voters at 16, in order to further enhance electoral equality among Union citizens. Currently, only Austria has the age threshold at 16 years. EPP disagreed with this, but lost the vote against the combined forces of the left, liberals and greens. The difference in this vote was made by 23 EPP Members who voted differently from the majority of their group and in favour of lowering the voting age at 16 – these Members come mainly from Austria, Ireland, Malta and Romania. Notably, in the ALDE group the Czech, Finnish and Spanish liberals have opposed the 16 years principle.

Joint EU-level constituency

The creation of a joint EU-wide constituency, in which lists are to be headed by each political family’s nominee for the post of President of the Commission was approved by 360 votes in favour to 237 against. EPP+S&D+ALDE+Greens/EFA pushed this through, but important disagreements were noted in the EPP (where the French, Hungarians, Swedish, Slovakians, Latvians, as well as two of Juncker’s Luxembourgish colleagues voted against). Notably, the British from across the political spectrum opposed (conservatives, socialists, greens, eurosceptics).

Chances of being adopted and possible consequences

If adopted, the rules will be a big leap forward towards “Europeanisation of the European elections”, which until now have been seen as “second-order national elections”. It is precisely because these elections are seen as secondary that the new rules may actually get some traction, as the national politicians may feel that they don’t give away too much. However, it is hard to believe that unanimity will be reached in the Council to set into law some of the requests.

The biggest issue which will face opposition in the Council is the nomination of a leading candidate (for the Presidency of the Commission) by the European political parties, which has very small chances of passing in the current composition of the Council, which includes prime-ministers Cameron and Orbán, who also opposed Juncker’s nomination. Moreover, the newly elected Polish Prime Minister, Beata Szydlo, has reinforced the opposing camp. However, if the text will not specifically say “candidates for the European Commission Presidency”, but simply “leading candidates”, this would still have a chance.

Secondly, there is the issue of the electoral thresholds, which will be disputed in countries such as Germany, where the Constitutional Court has abolished the threshold for the 2014 European elections. However, if the new rules will be stated in an EU law, the position of the Court is likely to be different.

Last year, with the eventual appointment of President Juncker as head of the Commission, the EU Parliament has shown that it can be truly powerful when there is a strong majority behind a decision, so this Hubner-Leinen report has to be taken seriously. On the other hand, this time around (unlike in the case of Juncker’s appointment) the Council will decide by unanimity, which is a completely different thing. Consequently, at this stage we can expect that the softer changes may eventually become reality (if not de jure, then de facto, as in the case of the spitzenkandidaten process in 2014).

All in all, the provisions from this report can hardly be assessed separately, but rather in conjunction with the broader debates on reforming the institutional setting of the EU and, inevitably, the Brexit.

For more information, contact me at [email protected] or on Twitter at @dorufrantescu.

Source: Votewatch Blog – Doru Frantescu’s Posts

Be the first to post a comment.