Blog

with special thanks to professor Simon Hix and research assistant Davide Ferrari

—

After the outcome of the Brexit referendum, many observers wondered how the equilibrium of powers in the EU Council would change. We have looked at the voting dynamics over the last 7 years (over 22.000 votes of EU governments) to understand what is likely to happen after the UK leaves.

Our analysis is based on the same dataset and methodology that indicated that the UK was increasingly outvoted in the Council in recent years, thus predicting the centrifugal policy orientation of the British government. Now, we are using the same type of analysis to predict what will happen next.

Understandably, the behaviour of the remaining countries vis-a-vis each other once the UK departs may change substantially. However, we thought relevant to show what the current situation is. This is what we found:

Germany is far more outvoted than France and Italy in the Council

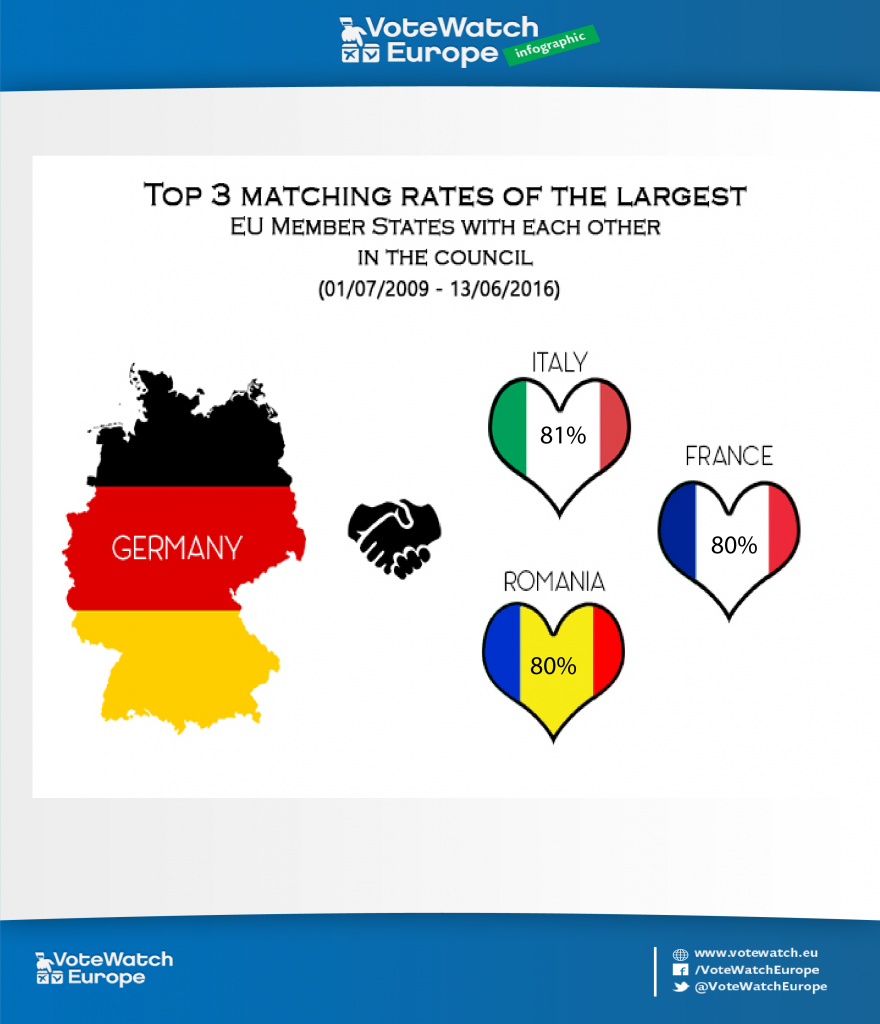

While Germany is a huge economic power and one of the main drivers of EU integration, the politics in the EU Council is less about the economy and more about diplomacy and negotiation practices, which lead to building coalitions to form majorities (or blocking minorities). What a country needs in the Council in order to be successful is to find allies with similar positions. In this regard, decision-making data since 2009 indicates that France is in a better position to build majorities than Germany.

Concretely, since 2009 Germany has been outvoted 42 times (especially on environment, internal market, transport and civil liberties), whereas France only 3 times (environment). For instance, Germany has been outvoted on antitrust and intellectual property legislation.

Most observers would argue that Angela Merkel is in a stronger political position at home and plays a more active role in Europe than Francois Hollande. However, only the general principles of the EU policies are decided at the level of the heads of states, while the nitty-gritty policies are negotiated and put into place by the armies of civil servants representing their governments in the myriad of working groups of the Council. While these civil servants have almost insignificant political power overall, they can exert enormous influence on their specific dossiers and areas they are experts in. They, and their bosses in the COREPER, are the ones preparing the content of the legislation and building alliances to reach a majority or a blocking minority.

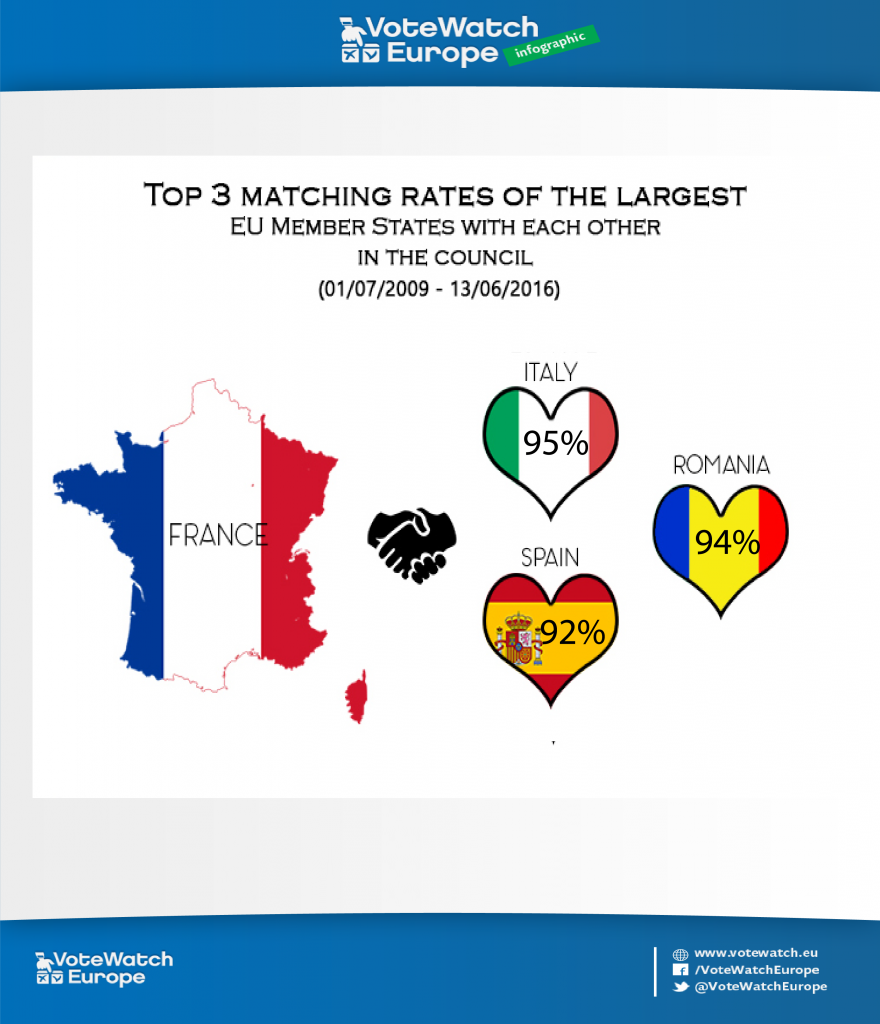

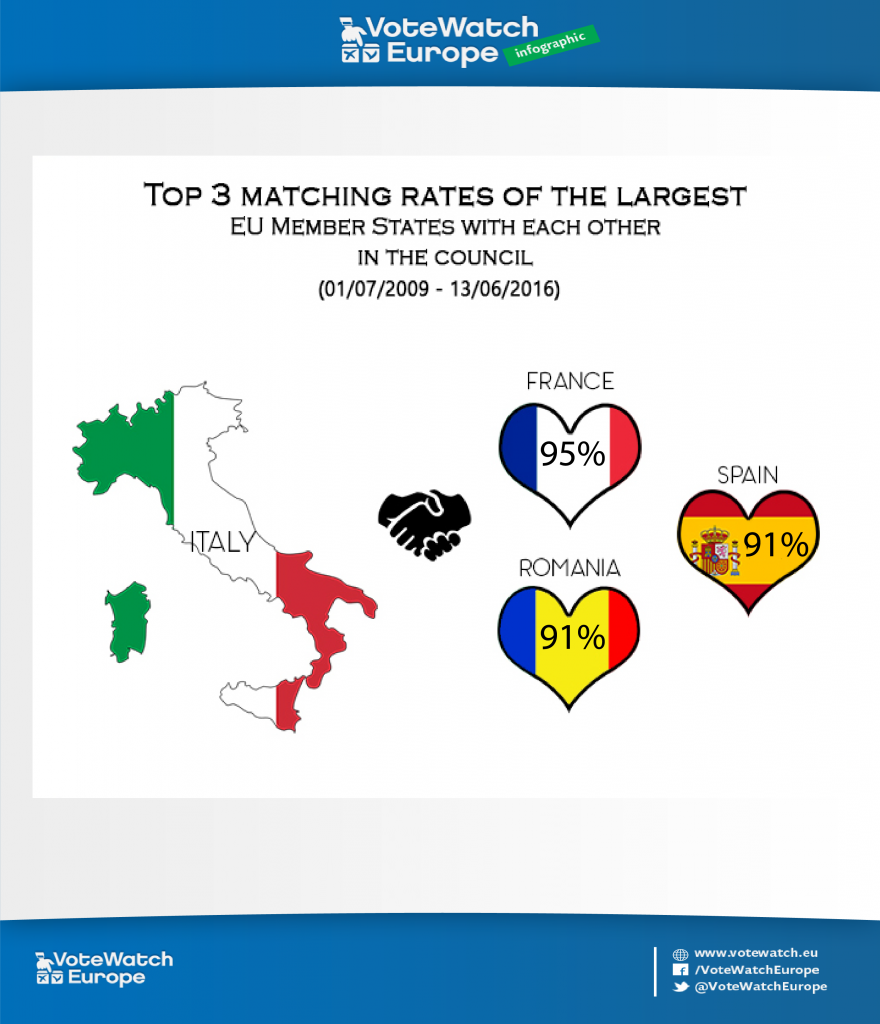

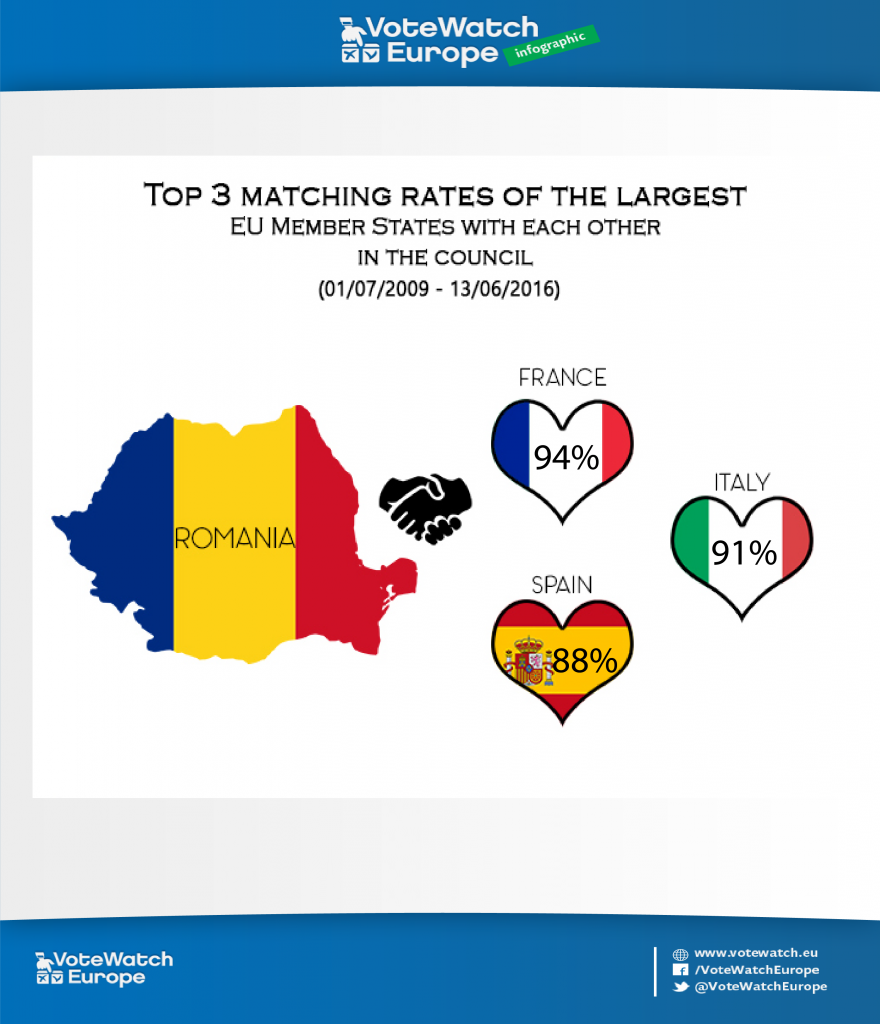

Coalition-formation data indicates that France has a close ally in Italy, with whom it has voted together in 99% of decisions since Matteo Renzi became Prime Minister. Italy, for its part, has been outvoted 11 times since 2009, but mostly when Silvio Berlusconi was heading the government, whereas the government led by Matteo Renzi has never been on the losing side in the Council so far.

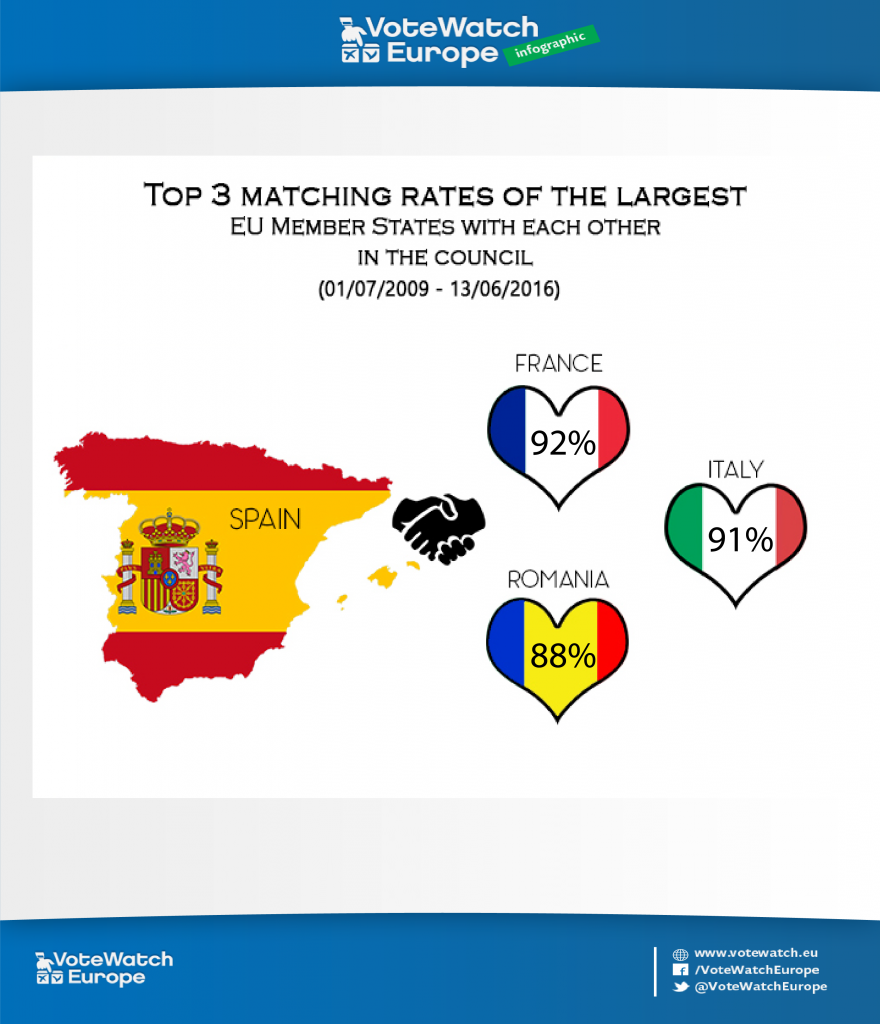

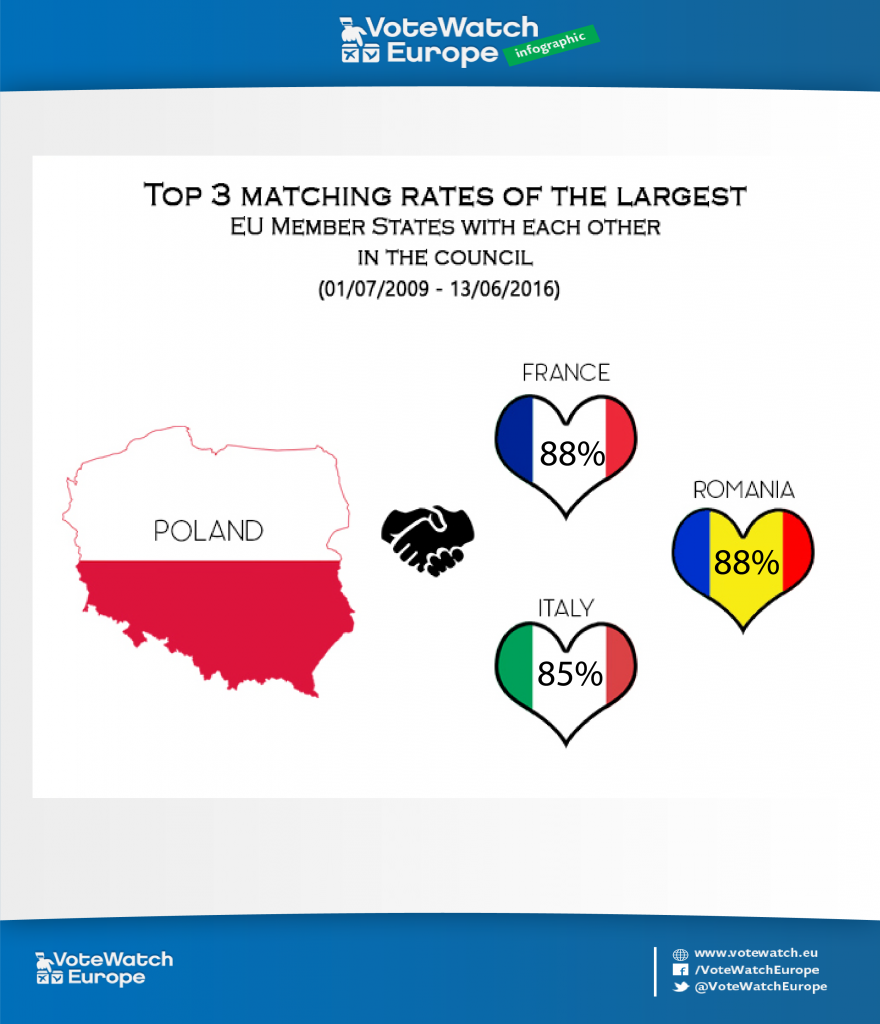

Also, the next biggest in size, Spain, Poland and Romania, all have better coalition scores with France than with Germany. One potential explanation of this dynamics may be that the French position is generally more moderate and easier to accommodate by the remaining Member States. Others argue that this is because the French diplomats are more fearful than the Germans to show that they have lost in Brussels and thus prefer to vote with the group when they see that they are going to be outvoted.

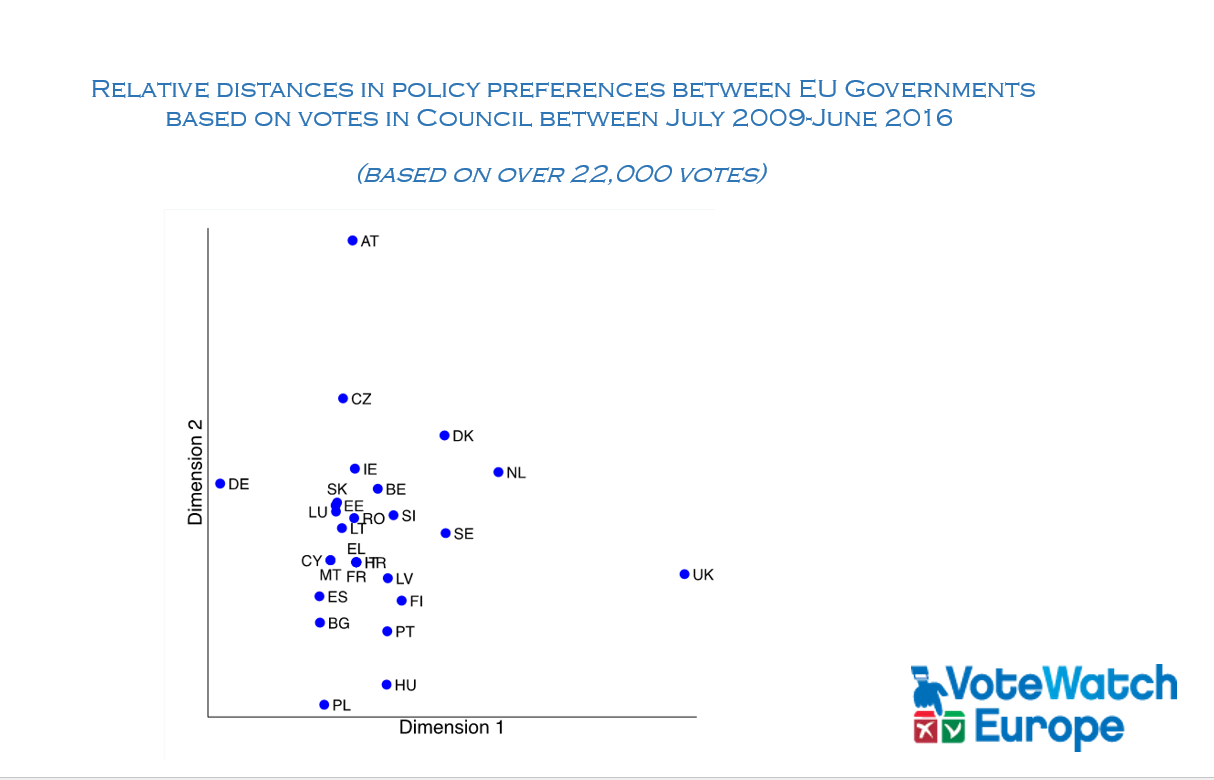

The picture below shows the relative distances in policy preferences between the EU Governments based on votes in the Council between July 2009-June 2016, including the UK (note: the two-dimensional pictures are simply an illustration of the two-country matching rates showing all matchings relative to each other).

The animation below shows the overall distances between the remaining 27 EU governments (once the UK would be out), suggesting possible clusters of countries (click to play the animation):

Without the UK, France and Italy are more likely to form blocking minorities

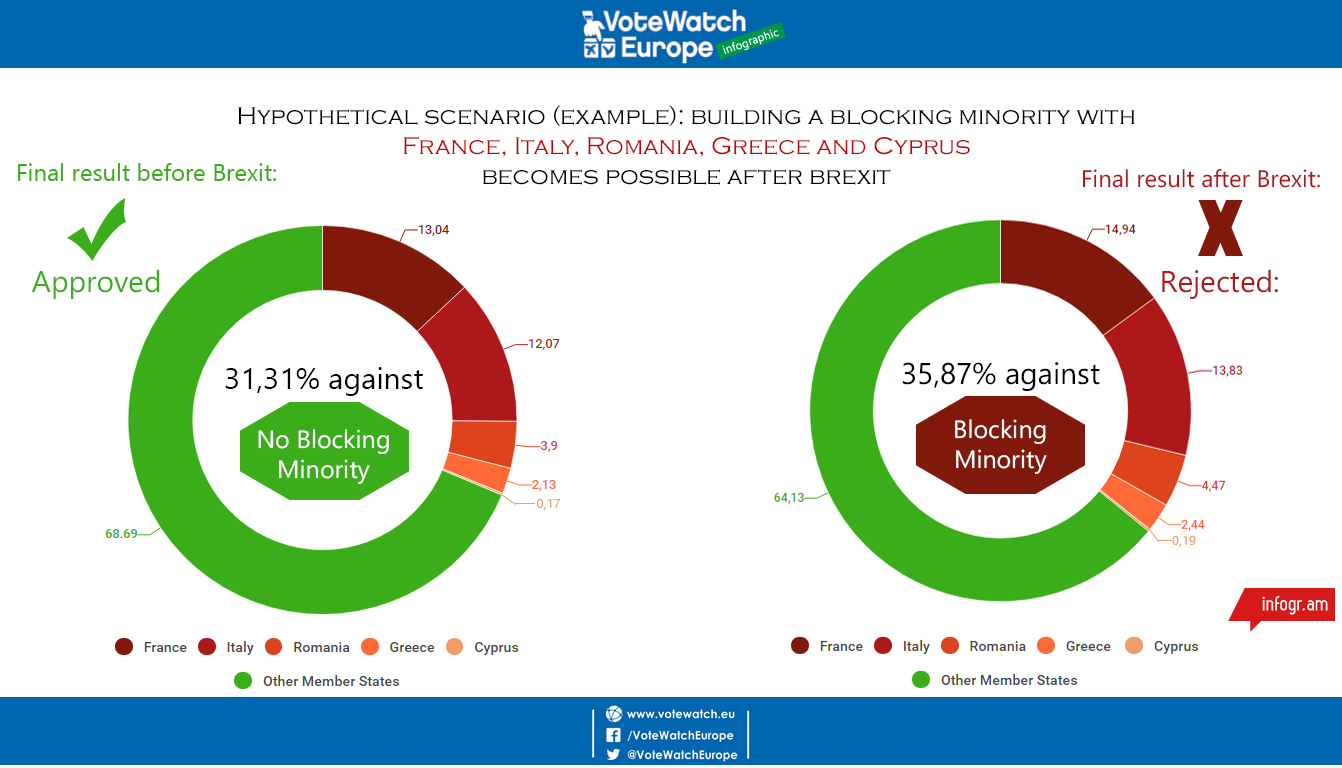

When Member States are in the minority, or want to push harder for their voice to be heard, they try to assemble a blocking minority, which has to be made up of at least 4 Member States representing 35% of EU’s population. This means that, usually, at least one of the largest Member States should be taken aboard in order to block a proposal.

With the UK out of the Council, and an increase in the share of weighted votes for the remaining countries, forming a blocking minority will be easier than now. However, the countries with more allies in the Council will benefit the most from it.

On the contrary, Germany has a relatively low matching rate with the other large Member States, which means that, at the EU policy-making level, Berlin finds more difficult to establish a blocking minority. Instead, France, Italy and Romania have high matching rates with each other. Therefore, without the United Kingdom, it might be easier for a coalition led by Italy and France to block whichever piece of legislation they do not like.

The infograph below illustrates how France and Italy will find it easier to build a blocking minority with just 3 other average and small countries after Brexit:

Coalition building in the Council seems to favour the countries promoting more EU integration

Considering the current debate on the future of the EU after the Brexit, the coalition data from the Council seems to reward the governments which more explicitly support a push towards further EU integration (Italy, Spain and France), rather than more cautious governments such as Poland, Sweden and the Netherlands. In fact, governments expressing criticism towards the EU are concerned about different policy fields: Central European governments are currently lashing out against the EU’s powers on migration, whereas the Netherlands and Sweden were outvoted the most on budgetary issues.

For this reason, even the countries that are more isolated (such as Germany, Austria and the Netherlands) are more likely to vote with France and Italy than with each other. Therefore, France and Italy seem better positioned at this point to hold the keys for the success of the legislative proposals in the Council.

Notably, the Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark are the governments who are losing the most after UK’s departure, as these three were the ones who most frequently have had the UK on their side.

All in all, the data set and methodology that we are basing our findings on is the same that indicated, since a few years ago, that the UK was going further away from the “EU’s center of consensus”.

Political affiliations of the governments influence their matching rates in the Council

Our data also shows that Poland has become more isolated over the last few months. Whereas Poland has been outvoted only 3 times from the mid-2014 to November 2015, the Conservative government has been outvoted 4 times over the last few months. This also shows that elections and changes in the governments in the Members States have an impact on coalition building dynamics in the Council.

Ideology plays a role: the already high matching rate between the votes cast by Italy and France has increased over the last 3 years, arguably influenced by ideological synchronising: Social Democrat governments at the same time in both countries.

However, the upcoming electoral processes in 2017 in France, Germany and the Netherlands (and the possible changes of governments) will play a key role in determining coalition dynamics in the Council. In fact, as previously shown, a change in the political affiliations of the governments would influence the relative positioning of these countries in the political spectrum of the Council.

The infographics below show the frequency of coalitions between the governments of the biggest Members States in the Council (except UK) between July 2009 – June 2016 (NB: consensual votes, ie. where there was unanimity, are excluded from this calculation). For more information contact me at [email protected].

Source: Votewatch Blog – Doru Frantescu’s Posts

Be the first to post a comment.