Blog

The European Parliament has recently said “no” to grant market economy status (MES) to China. At the final vote, 84% of its Members backed the EP document, which made it look to the outsiders like a broad consensus against MES for China. However, a closer look at the actual text adopted and on how MEPs voted on key amendments show a much more nuanced picture by country and political family.

As expected, Beijing is not happy with this result and subtly indicates that it might retaliate. China has made substantial investment deals with both the EU and its Member States, which EU political elites take into account when making a comprehensive analysis of the costs and benefits of whether to upgrade or not EU’s commercial relations with the Asian power. This analysis looks at the political dynamics behind this apparently technical decision.

There are differences among the EU political families

The final text adopted by the EP states that China is not a market economy and, as such, non-standard measures in trade investigations determining price comparability should be kept in place (read: applications of higher customs duties on certain products). However, the motion approved by the plenary does not explicitly state that a MES to China should be denied in case the five key criteria are not met (they are summarized here). Notably, an amendment to the joint motion that linked explicitly the grating of MES to the fulfilment of the 5 criteria was rejected.

In fact, despite the apparent broad consensus, there are nuances in the positions of the European political families on this thorny issue. In particular, the groups which are traditionally the most favourable to the principles of free market seem also the most favourable to upgrading trade relations with China. These are: the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR, the political family of David Cameron and Andrej Duda, governing over UK and Poland, respectively) and the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats (ALDE, whose members are leading the governments in the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Slovenia, Latvia, Estonia and Luxembourg).

This is shown by the motions tabled by the single political groups before the agreement on a joint motion: the motions by ALDE and ECR focused on the need for the EU to comply with WTO’s rules (read: to grant MES to China by the end of 2016). Additionally, ALDE and ECR did not mention in their versions of the document that China is not a market economy or that unilateral recognition of MES by the EU should not be granted. ALDE’s motion even recalled the importance of the trade with China for European economic growth and the creation of jobs.

Comparatively, the versions proposed by the European People’s Party (EPP), the Socialists and Democrats (S&D) and the Greens all mentioned explicitly that China is not a market economy. In this regard, the final joint motion is textually more similar to the ones tabled by the EPP and S&D (the two biggest political groups in the European Parliament). Notably, the EPP and S&D control the biggest share of EU governments, including big and average-size countries such as Germany, France, Italy, Spain or Romania.

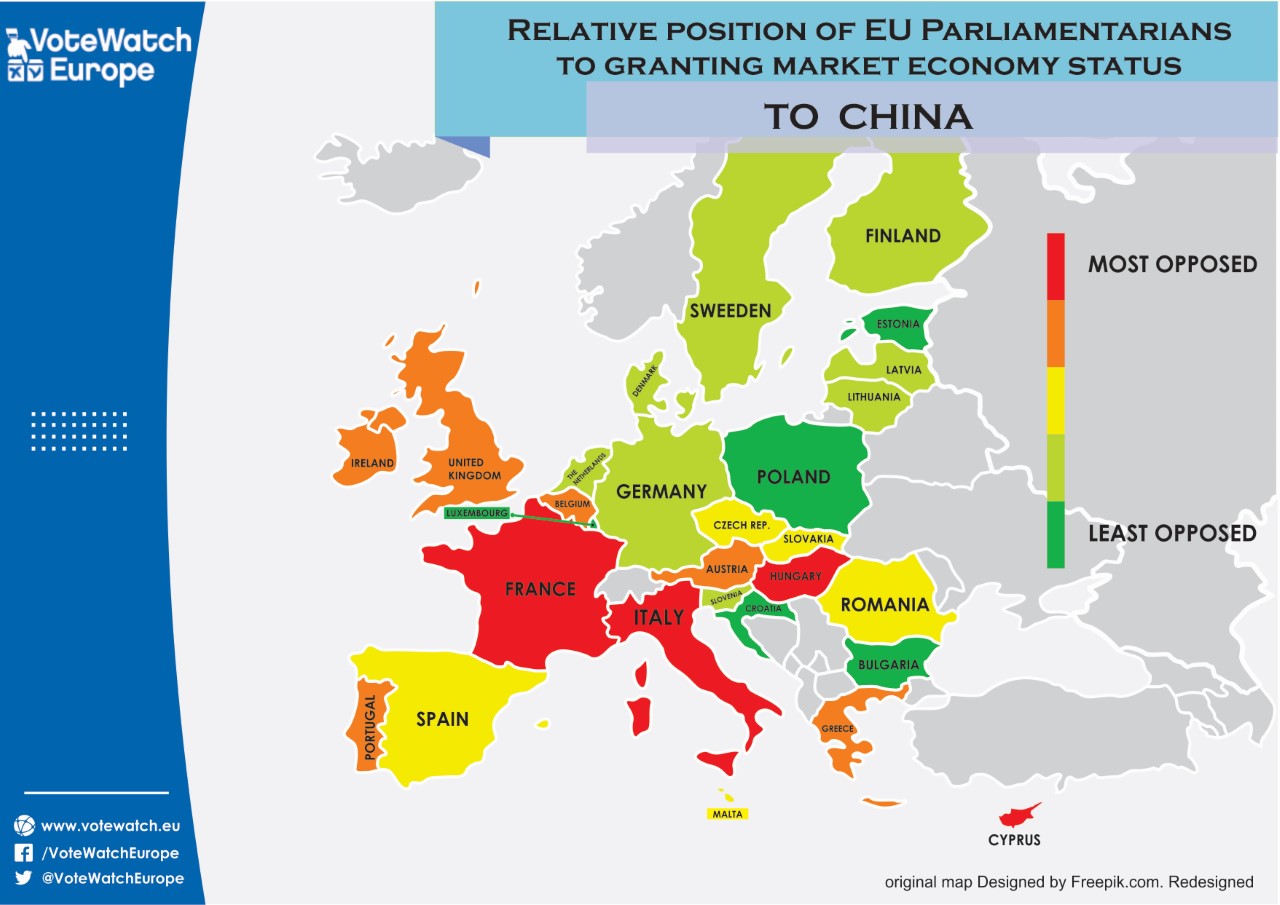

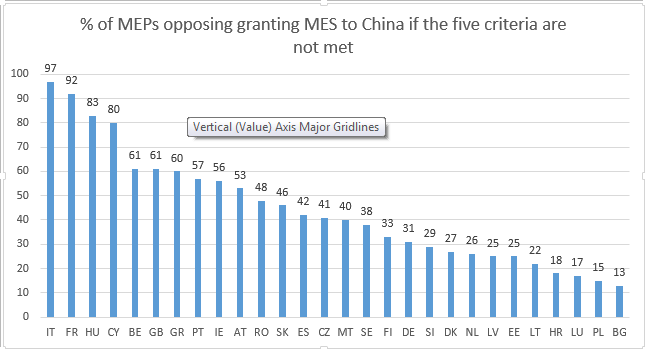

Italian and French MEPs lead the opposition to MES, the Polish and Dutch are among the least hostile

Our analysis of the debates and votes of the EU parliamentarians from a national perspective shows that Italian and French MEPs (from almost every political group) are the most active and vocal in their opposition to granting MES to China. At the other end, most Polish, Dutch and Swedish MEPs have shown a much more favourable stance. Interestingly, the Polish far-right leader Janusz Korwin-Mikke was the only one during the debate who praised the cheap steel coming from China and its potential benefits for European consumers. Overall, only 15% of Polish EU Parliamentarians are clearly opposed to granting MES to China, whereas this figure rises to no less than 97% in the case of the Italian EU Parliamentarians and 92% in the case of the French. Whereas Berlusconi’s and Renzi’s MEPs abstained on a hostile (to MES) amendment, French MEPs from every political group (with the exception of the far left) supported it.

Remarkably, the EU Parliamentarians of the French President Hollande (the French Socialists) were among the most vocal against the MES (they were the only ones in the S&D group voting in favour of a very explicit statement against China’s MES). It is worth noting that the French Socialists are generally opposed to free trade and they are also opposing the trade agreement with the United States (TTIP).

Also, the Hungarians of FIDESZ, which are the EU Parliamentarians of Prime Minister Viktor Orban, are not supportive of MES to China, despite the fact that the Hungarian Prime Minister is deemed to be tightening the bonds of his country with China. In this case, the protectionist attitude of Hungarian MEPs apparently played a more important role. In fact, Orban’s MEPs have also expressed strong reservations with regard to TTIP, even against the position of their fellow colleagues from the same European political family.

At the same time, the German parties do not seem to have a common position at this point. The Social Democrat Party (SPD, junior coalition partner in Merkel’s government) followed its political group’s line and decided to abstain on the critical amendment. For their part, Merkel’s own EU Parliamentarians (the largest delegation in the EP) did not support the critical amendment, although they still backed the joint resolution stating that China is not a market economy. The hesitations of the German politicians can be explained by the different interests of various sectors of their society: while Germany’s labour force seems to be among the most exposed to upgrading commercial ties with China, Germany-based importers are among the main beneficiaries of reducing custom duties, also considering that the port of Hamburg is the second biggest point of entry for Chinese goods into the EU.

Speaking of ports, Rotterdam is number one in this respect, which perhaps explains the small appetite of Dutch politicians to oppose MES for China.

Divisions among Member States are also observed when looking at the positions of the various eurosceptic parties. Whereas most eurosceptics, in particular the Italian ones, are strongly opposed to opening the market to Chinese competition, the Polish Congress of the New Right, the Dutch Party for Freedom and the German Alternative for Germany did not follow their groups’ position on this issue (i.e. they were more favourable to the MES for China).

China’s diplomatic offensive has brought mixed results

The government in Beijing is more than anxious to get the EU’s anti-dumping measures out of the way of its exports to Europe. After decades of impressive economic growth, China is now facing less promising perspectives. The changing trends in global trade have led China to face over-capacity issues, ie. China needs markets to get rid of its stocks. Remarkably, China even faces a demographic problem (ageing population) which threatens the very core of its (ideologically-based) social policies and this has been made clear by the abandon of its traditional one-child policy.

President Xi Jinping has come to power only recently (2013) and needs concrete results to consolidate his leadership. His unprecedented internal anti-corruption campaign has helped in this respect for now, but on the long run it is the overall state of the economy that will make or break. In anticipation of the future trade opportunities, since 2013 China has also developed pilot free trade zones on its Southern and Eastern coasts (Shanghai, Fujian, Guangdong).

Interestingly, China sees the establishment of trade blocks by the West (TPP, TTIP, EU-Japan FTA, etc.) as a form of macro-regional protectionism (whereas Europeans see them as liberalisation of trade) that would leave China outside the main pitch. Consequently, Beijing is sensitive about EU’s next moves and, in anticipation, has been playing the “carrot” card, promising considerable financial support for projects in the EU. On the one hand, we’re talking about Chinese massive participation in Juncker’s investment plan.

On the other hand, China has tried to strengthen bilateral relations with EU’s Member States both in the West and East. President Xi Jinping has met successfully with David Cameron, inaugurating a new “golden era” in the China-UK relations. The meeting has also resulted in a concrete deal to build new British nuclear power capacity with Chinese and French resources. Angela Merkel has followed suit, signing a deal to sell China 130 jets manufactured by Airbus. Separately, China and the countries in Central and Eastern Europe have recently established a 16+1 forum for yearly meetings at intergovernmental, business and think tanks levels.

However, as the vote in the European Parliament has shown, all this doesn’t mean that European political elites find it easier to substantially upgrade EU’s commercial ties with China, given other types of pressures coming from within their societies (or from other international players) that counterbalance these efforts.

Perception of Chinese economic power and level of imports influence the opposition to MES

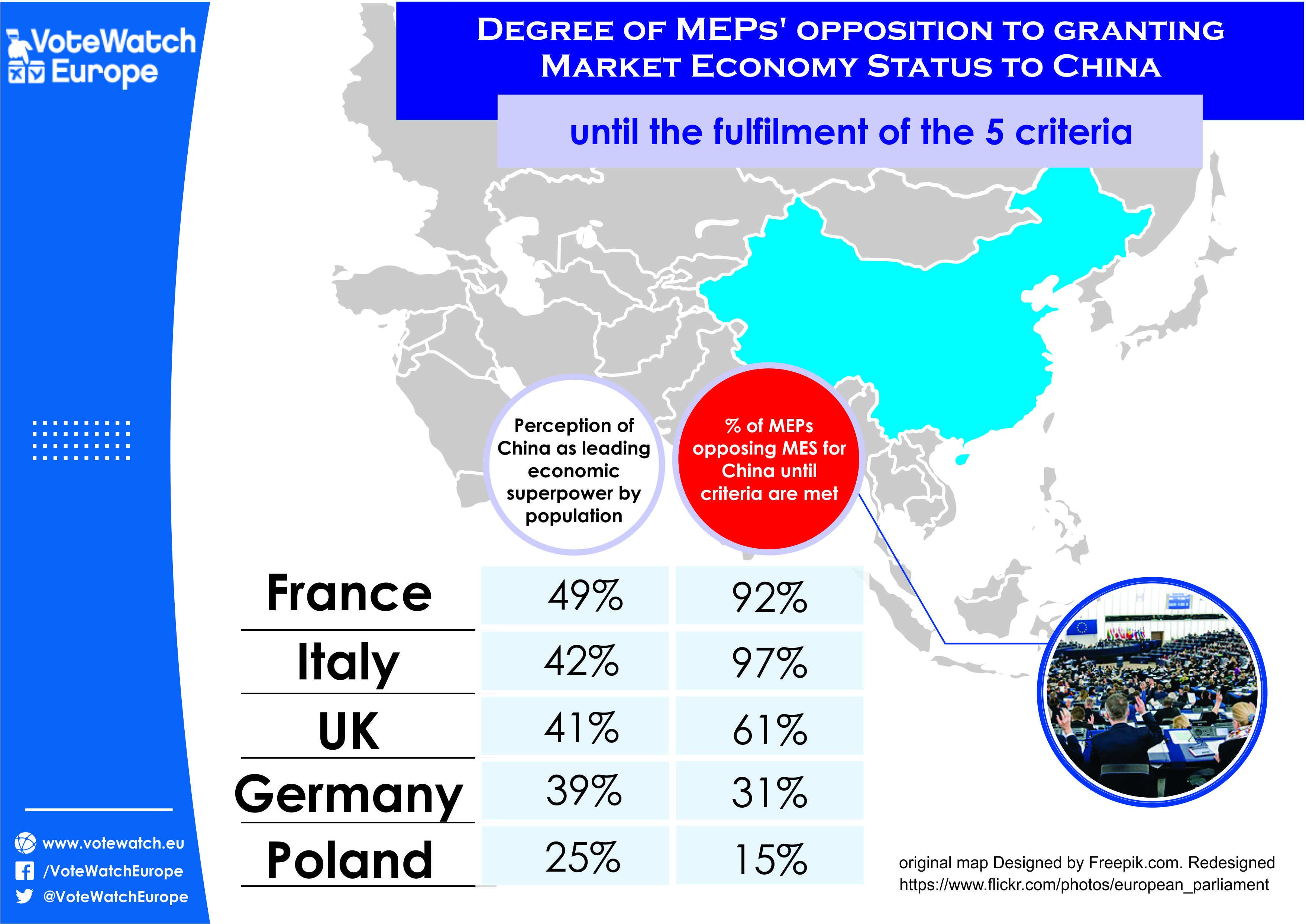

The national attitudes towards protectionism, rather than a negative perception of China, is a stronger driver of the opposition of certain countries to granting MES to China. In fact, according to the Pew Research Center’s Global Indicator on China, French people have a way more positive perception of China (50%) than German ones (34%). The fact that the signs in the Charles de Gaulle airport in Paris are also in Chinese is illustrative for the strengthening of the relations between China and France.

Remarkably, Germans hold the most negative perception of China across the European countries surveyed. However, when it comes to the perception of Chinese economic power, more French (49%) and Italians (42%) see China as the leading economic superpower than Germans (39%) and Polish (25%). Consequently, it seems that, when shaping one’s view on whether to open the European market to China, the perception of China as an economic threat weighs more than the overall perception of China’s image (which also includes its track record on human rights).

Interestingly, the risk to the European labour market (ie. people losing jobs) as a result of granting MES to China does not seem to be directly correlated with the politicians’ views. In fact, a recent research shows that the German and Polish economies would be way more negatively affected (in terms of share of employment at risk) than the French one. Still, the French politicians are more protectionist than the German and the Polish ones.

This apparent paradox can perhaps be explained if we take into account the role and the influence of the importers (EU citizens/companies importing and trading Chinese goods). In fact, the levels of import from China to Germany (10%) and the Netherlands (14%) are far higher than the French (8%) and Italian (5%) ones. Indeed, importers’ associations such the Foreign Trade Association have always been critical of anti-dumping measures and are now advocating for granting Market Economy Status to China. On the other hand, steel associations are urging the EU to denying MES to China and thousands of demonstrators recently gathered in the Schuman Roundabout, just in front of the European Commission.

Member States attitudes on trade defence reform reflect their approach to MES for China

The positions of the different European countries on trade defence are particularly important, as the final outcome on China is also linked to the reform of the European trade defence tools. One of the sticking points of this reform, which is currently stuck in the Council of the European Union, is the limitation of the application of the lesser duty rule in certain circumstances, such as structural distortions or significant State’s interferences in certain sectors or insufficient levels of social and environmental standards. To put it in simple terms, not applying the lesser duties rules would allow the European Commission to apply higher anti-dumping duties on imported products (a more detailed explanation of the issue is available here). Not surprisingly, the positions of MEPs on the proposed reform mirror their positions on granting MES to China (except for the Polish ones and few other cases). For example, in February 2014, a great majority of Italian and French MEPs voted for limiting the lesser duty rule as much as possible, whereas few of the Danish or Swedish supported this.

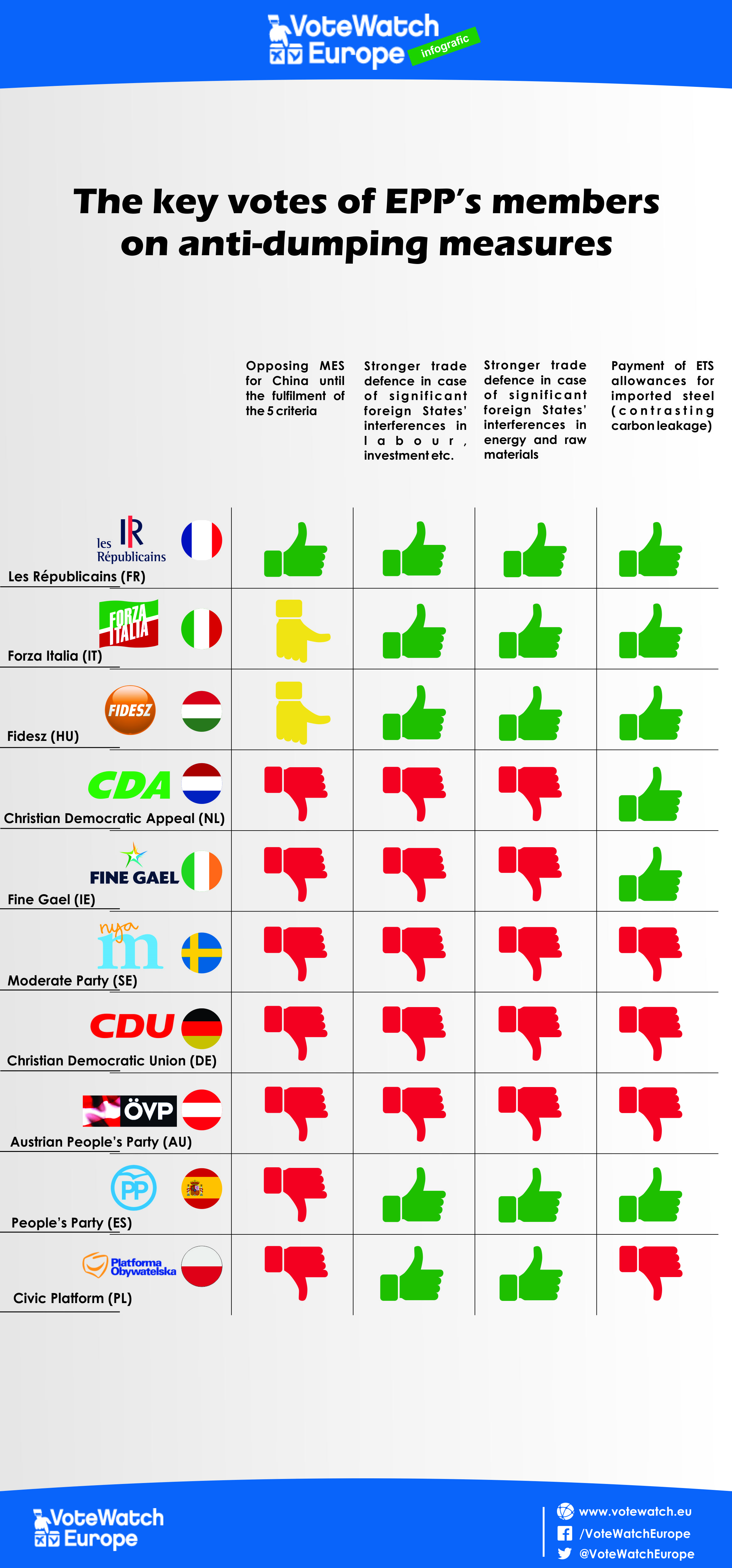

The strong impact that these rules, decided by the EU, have on the national markets is highlighted by the noticeable divisions among the EU Parliamentarians of the EPP (which are otherwise a very united political family). As it is shown in our infographic, the EPP is constantly divided along national lines on trade defence, with the Italian Forza Italia (Berlusconi), the French Les Républicains (Sarkozy) and Hungarian Fidesz (Orban) leading the protectionist front, whereas, the German Christian Democratic Union (Merkel), the Austrian People’s Party the and the Swedish Moderate Party are strong advocates of free trade.

In order to break the deadlock, France and Germany recently drafted a joint letter, calling for a swift and balanced modernization of trade defence. However, the reform will have to overcome the opposition of 14 Member States, such as the Netherlands, Austria and the UK, which formed a blocking minority in the Council against the changes to the lesser duty rule. According to the media, in some of the sceptical countries, such as Belgium and the UK, the opposition to the change to the lesser duty rule has gradually softened. In the last parliamentary vote on MES for China, as much as 61% of UK’s MEPs backed denying MES for China unless the five criteria are met. The UK’s case is particularly interesting, as in the same parliamentary term, only 39% of UK’s MEPs backed the imposition of ETS allowances on imported steel in order to create a level playing field between domestic and foreign production of steel. However, in this case, the change in attitude mainly regards the parties in the opposition (such as UKIP) and not the Conservative party, which is still loyal to its pro-free trade attitude.

Background information

By the 11th December 2016 the Commission will have to decide how to deal with the expiry of Article 15(a)(ii) of China’s accession to the WTO, which currently allows WTO’s members to treat China as a non-market economy and consequently apply non-standard methodologies to the application of duties on Chinese products. The Chinese government claims that after that date, the EU is obliged to recognize the country as a market economy. If the European Union decides to grant China a Market Economy Status, the current antidumping measures (e.g. special tariffs) applied on Chinese products will no longer be available. However, such a decision would have a negative impact on certain Member States’ economies in terms of jobs and growth, as it would severely hit some industrial sectors, such as the steel industry, which is already suffering because of Chinese competition.

Legal experts are divided on whether or not the EU is obliged to grant Market Economy Status to China. Whereas some experts are of the opinion that China should still meet the five criteria established by the EU for a country to be recognized as a market economy, others claim that such a decision is legally feeble and could be challenged by China in front of WTO’s Court. Additionally, a potential trade war between the two economic superpowers would hit other industrial sectors, as well as further undermining the credibility of the WTO.

A third option would be to grant MES to China, but only with the contemporary adoption of other mitigating measures and the upgrading of the European Trade Defence System. This option would allow the EU to avoid a conflict with China, but still to protect its industry (also making use of the room available in WTO’s rules). Still, there are concerns about the political will of Member States to approve the proposed reform of the Trade Defence, as the proposal of the Commission (already amended by the European Parliament) has been blocked for two years in the Council because of disagreements between the national governments.

For more information, contact us at [email protected].

Source: Votewatch Blog – Doru Frantescu’s Posts

Be the first to post a comment.