Blog

Over the past few weeks, calls for more integration and coordination in EU Defense policy were elevated from several powerhouses. But what are the real chances of this project? This report measures the level of support from political forces across the EU, the balance of power between them and shows who are the allies of the European Defense Union project, who are its opponents and who are the (flexible) undecided.

The French and German defense ministers called for a shared Permanent European Military Headquarters along with the establishment of Permanent Structured Cooperation, otherwise known as PESCO. In Bratislava, all 28 Member States’ defense ministers met to discuss their plans for integrated European Defense. The French and Germans brought their proposal to the meeting, and, with Italy and the Visegrad group (Poland, Hungary, Czechia, Slovakia) explicitly expressing their support, some observers might be tempted to consider the Defense Union as an easy sell.

However, our mapping on the positions of political support across the EU for the defense union shows that opposition is stronger than one might think just by watching the media and that the UK is not alone in its skepticism towards the proposal. We used the votes of the Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) to track and measure the views of all relevant political forces across the 28 Member States, taking advantage of the fact that the EP gathers representatives of parties coming from both government and opposition. Moreover, MEPs are free to vote according to their real views, as they are not constraint by the need to support their government’s position, which provides us with a more accurate picture.

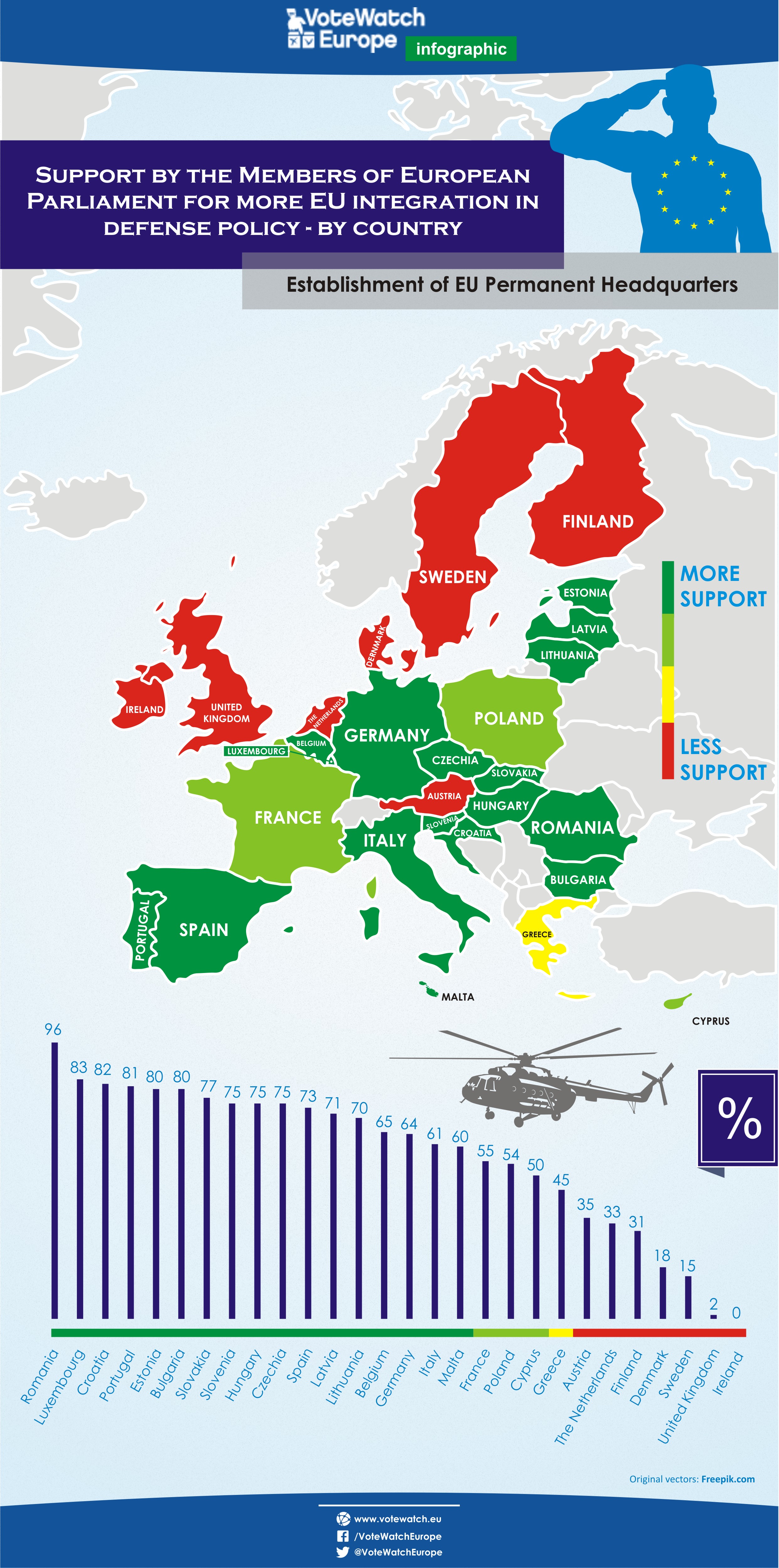

Although a solid majority of EU Parliamentarians from several Member States are supporting this proposal, the geographical cleavage emerging from our analysis seems clear, as (with the exception of the Baltic States) most of the parties from all the Northern Member States oppose the establishment of Permanent Military Headquarters of the EU. These countries are either neutral states (non-NATO), such as Sweden, Finland, or have a historical tradition of neutrality, such as Denmark and the Netherlands.

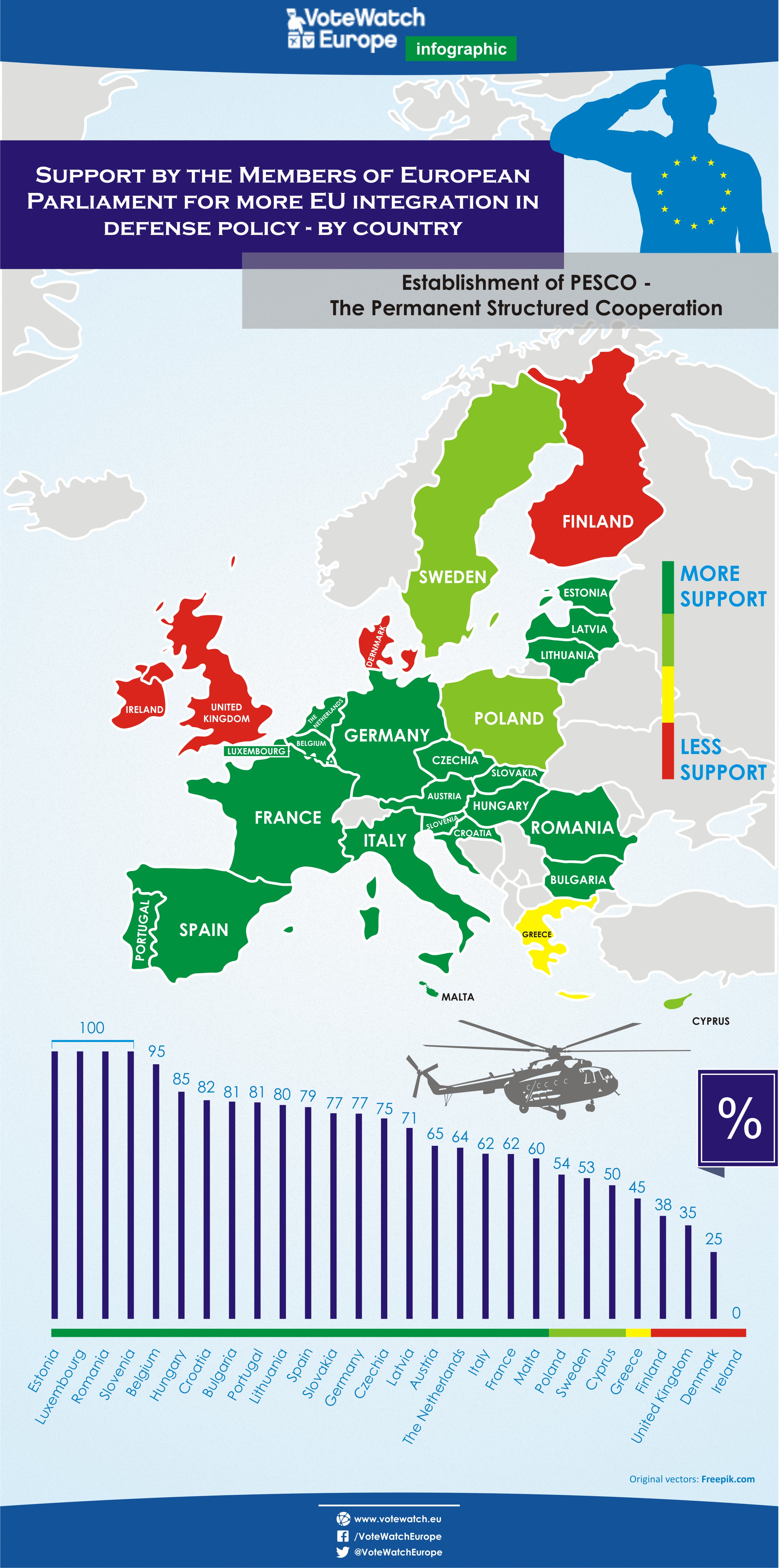

Our report also shows that there are different degrees of opposition to the key aspects of the Defense Union. For example, the establishment of PESCO is less controversial than the permanent EU headquarters and some neutral countries would support their use.

–

Why now?

The further development of the European Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) is by no means a new topic, and the EU has not taken the opportunities to shape such strategies in a comprehensive way yet. The question that arises is what, if anything, makes this attempt different and what are its chances of success?

First, we need to set the scene of the calls. Like never before, Europe appears to be facing a crisis around every corner- from economic stagnation, to terrorism, refugees, and an unstable Middle East alongside an increasingly threatening Russia.

The volatile international environment requires the EU to overcome deadlocks and move towards becoming a global power. Through its calls for common EU headquarters, the European Defense Fund and common military assets, Juncker is once again drawing attention to an opportunity to strengthen the security of Europe.

But well intentioned calls and projects from the European Commission and expressed support from the Parliament are not enough to secure the future of a European Defense Union. The EU track record has shown that the biggest impediments to progress are in fact of national nature. Recently, the overall tone surrounding these issues appears to have changed, especially in Germany, France, Italy and the Visegrad group. On several occasions, Washington has also signaled support for an increased European involvement in their defense matters.

Alongside the turmoil in NATO’s second largest contributor, Turkey, and the growing possibility of the election of Donald Trump as the next American President (whose speeches triggered alarms amongst Eastern NATO members amidst fears that article 5 may not be respected by the US), this shift in EU policy might be a welcomed development. Not only would it show that Europe remains united in times of crisis and following Brexit, but more so that the EU is willing and able to take charge of the European defense.

–

Large support for the Permanent Defense Headquarters across the largest EU Member States, but it faces considerable opposition from fringe parties

The MEPs coming from Germany, Italy, and Spain all demonstrated high levels of support for the establishment of a Permanent EU Headquarters in these countries.

In fact, Italy took the hardest stance on defense integration with a plan extending past the scope of Germany and France’s proposal. Unlike Paris and Berlin, Rome has suggested that there should be a permanent military force in addition to the permanent military headquarters. However, the Italian proposal seems to go too far to be accepted by the more skeptical Member States. Additionally, although the Italian parties sitting within the ranks of Renzi’s Democratic Party (S&D) and Forza Italia (EPP) are supporting more EU integration in defense policy, notable opposition comes from the Eurosceptic 5 Star Movement (EFDD) who is on the rise (has recently won elections in the capital Rome) and challenges Renzi’s governing position.

In France, while the government is one of the main supporters of the defense union, it faces some opposition at home. In fact, support for the Defense Union among the French comes from the moderate French parties (namely the Socialist Party of president Hollande, the Republicans of Sarkozy and the smaller centrist parties), whereas Marine Le Pen’s rising National Front, the Greens and far left parties reject the idea of integrated defense (and voted against the defense headquarters).

Instead, in the German case, the Greens supported the initiative, although not everybody is enthusiastic about this project on the left side of German political spectrum. In addition to the opposition of The Left (GUE-NGL), quite a few MEPs from SPD (S&D) decided to abstain (at the beginning of the year they were outright opposed). On the opposite side, the rising Alternative for Germany (ENF – EFDD) is also rather hostile to this new project.

–

Central and Eastern European MEPs are the Firmest Supporters of More Integration in Defense Matter

Notably, former Russian satellite states in Eastern Europe strongly support the creation of the Permanent Defense Headquarters. Overall, Romanian politicians are the most supportive of the defense integration (judged by the behavior of their MEPs). Romania currently has a president with German ethnic background and a prime minister seen as France-friendly, which showcases (and may contribute to) the orientations of this second largest Eastern European EU member state.

The case of Poland is, however, remarkable: the Polish Conservative MEPs of Law and Justice voted against the proposal for a Defense Union, which is in stark contrast with the recent statements made by the Polish government. This may indicate that the policy orientations of the Polish government are fluctuating due to internal disagreements and are yet to be clearly defined.

Estonia and Latvia are geographically vulnerable to perceived Russian aggressiveness, which explains their unconditioned support for the new establishment. 71% of Latvian MEPs favor the creation of the headquarters, as well as 80% of Estonian MEPs.

–

The UK is the main obstacle towards the establishment of Permanent Military Headquarters

Further integration of European defense will rely on both the British Isles and the neutral member states. Following the referendum in June 2016 and the decision to leave the European Union (Brexit), the UK – a keen supporter of the ‘less is more’ approach, could soon become the first country to leave the EU. From the perspective of the CSDP project however, Brexit is actually a positive development, as the UK is known to be one of the main ‘breakers’ to the further development of the project and in general to a deeper integration of the EU.

Despite the UK’s vote to exit the EU, British Defense Minister Michael Fallon attended the recent defense ministers’ meeting in Bratislava. Fallon expressed Britain’s opposition to the permanent defense headquarters in stating that “Europe is littered with headquarters, the last thing we need is another one.” This is in accordance with Fallon’s claim that Europe needs a stronger defense to deal with terrorism and migration, yet believes participating in NATO is the best way to defend Europe.

The British are so adamant in their opposition to integration that from the entire British EP delegation, only the MEP from the LibDem supported the initiative, whereas all the other MEPs were either unenthusiastic or outright hostile.

–

The Neutral Countries: Unified in Opposition to the Defense Headquarters

As shown by our map, there is still further opposition to this initiative across Europe. In particular, neutral countries are far from being enthusiastic about these new projects. However, there is a clear difference between the views of center-right wing parties from neutral countries and the ones of center-left wing parties.

In fact, in the EPP the support for the establishment of Permanent EU Headquarters is particularly high, even among the Maltese, Austrian, Finnish and Swedish MEPs. The members of the Irish party currently in government, Fine Gael (EPP), are the only exception, although Ireland is a quite special case, given that none Irish MEP supported the initiative.

Higher is the opposition among neutral countries’ MEPs in S&D: the Austrian S&Ds abstained from voting on the formation of a permanent defense headquarters for the EU, whereas the Swedish Social Democrats even rejected the proposition.

Sweden’s neighbor, Finland, also joined the resistance as two parties currently in government in Finland opposed the initiative. Finland’s Centre Party (ALDE), led by Finnish PM Juha Sipilä, voted contrary to their colleagues in ALDE and opposed the creation of the new headquarters.

In the run-up to the Council of Ministers meeting, Finland even came out with its own proposal: rather than suggesting the establishment of a permanent EU military headquarters, Finland proposes a joint civilian-military capability in order to facilitate collaboration between the Member States without having capabilities solely under the EU flag. This is a softer approach than the other three states are taking, although it is still a step in the direction of an increased cooperation.

In addition to the neutral countries, the Netherlands and Denmark (which were both neutral countries until the Second World War) added strength to the opposition of the defense headquarters. Both the Danish Venstre and the Danish Social Democrats abstained from voting, whereas the Eurosceptic Danish People’s Party voted against. Among the Dutch ranks, the party of Prime Minister Mark Rutte-the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy- voted the headquarters down, a clear demonstration of the strong Dutch reticence on defense integration (the two largest Dutch parties in the polls – the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy and the Party for Freedom- oppose the initiative).

National interests are hindering the use of Permanent Structured Cooperation

In addition to setting a new landscape with the creation of the European External Action Service and the position of High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, the Lisbon Treaty laid down several procedures and mechanisms through which Member States who wish to pull their defensive capabilities together under one common umbrella can do so with greater flexibility.

One of these procedures is the so called ‘pasarelle’ clause which allows the Council to act by qualified majority (QMV) in aspects related to a startup fund for military and defense operations, the European Defense Agency. In practice, however, unanimity has remained the lingua franca.

The deadlock is mostly of political nature, as these issues are perceived to be national prerogatives by some Member States who fear that advancing the CSDP will lead to a European army and the possible creation of a ‘two-speed’ Europe. As a result, instruments such as the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) or the mechanism for enhanced cooperation are bypassed due to the increase political controversy surrounding them.

–

PESCO’s relative popularity

Yet, as a whole, the European political forces seem to be more comfortable with the idea of establishing Permanent Structured Cooperation than the Permanent Defense Headquarters. A large majority of MEPs (66%) supported the establishment of PESCO. Among the largest national delegations, German, French and Italians remain the major supporters of this initiative, just as they were for the permanent defense headquarters. Also in this case, France, Italy and Germany can count on the strong support of Central and Eastern European representatives for deepening the level of integration in European matters.

Suggesting that there is a possibility for integrating European defense, also a comfortable majority of MEPs from Sweden, the Netherlands and Austria voted in support of establishing Permanent Structured Cooperation. The Finnish disagree with PESCO too: most of the Finnish MEPs oppose PESCO as a means of integrating European Defense. Remarkably, even in this case the Finnish Centre Party displayed substantial sensitivity towards the issue, being one of the few parties in the ALDE group who voted against PESCO.

–

Likely outcome: slow progress towards more defense integration

As it looks like at this point, the high opposition to the establishment of Permanent European Headquarters coming from neutral countries, added to some degrees of internal skepticism, entails that the Franco-German initiative will only pass if either the proposal is watered down to some extent or exceptions for neutral countries are provided (two-speed Europe). On the other hand, smaller initiatives towards more cooperation are more likely to pass, as they are also fueled by the several external challenges that the European Union is facing.

—————–

About the authors:

Doru Frantescu is cofounder and director of VoteWatch Europe (the think most followed by the Members of the European Parliament).

Eva Chitul is adviser at IDA Group.

To get a detailed mapping of the views of EU’s political parties and individual politicians, or to find more about our projects, contact us at [email protected].

Source: Votewatch Blog – Doru Frantescu’s Posts

Be the first to post a comment.